The Running Movie

Liner notes for a lost sports film.

In 2019, Mike Russell decided to spend a year training for the Dipsea Race, inspired by a movie he’d seen as a teenager in 1986.

But the race kept getting pushed back during the pandemic. So Russell pursued a new goal: interviewing people who made the movie that inspired him.

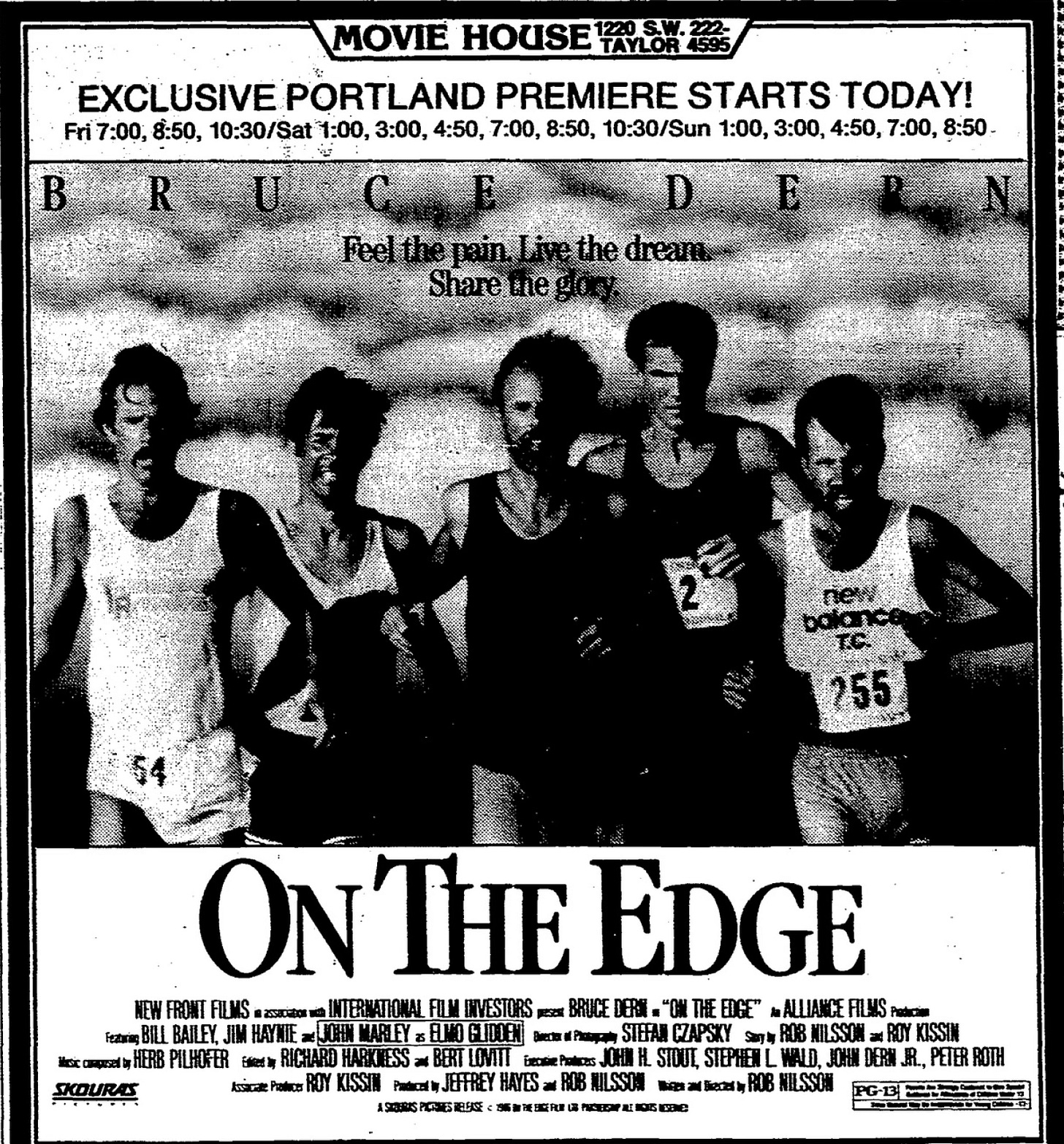

Here’s a brief history of writer/director/runner Rob Nilsson’s “On the Edge” — a beautiful, offbeat, nearly forgotten cult film about an aging runner (Bruce Dern) who tries to stage a solo comeback, only to find community on the trail.

“From one thing, know ten thousand things.” — Miyamoto Mushashi

“I love running cross country. On a track, I feel like a hamster.” — Robin Williams

I remember the moment the movie grabbed me. It was the shot where he ran up Bolinas Ridge.

It happened at minute 10. The previous minutes transpired as follows:

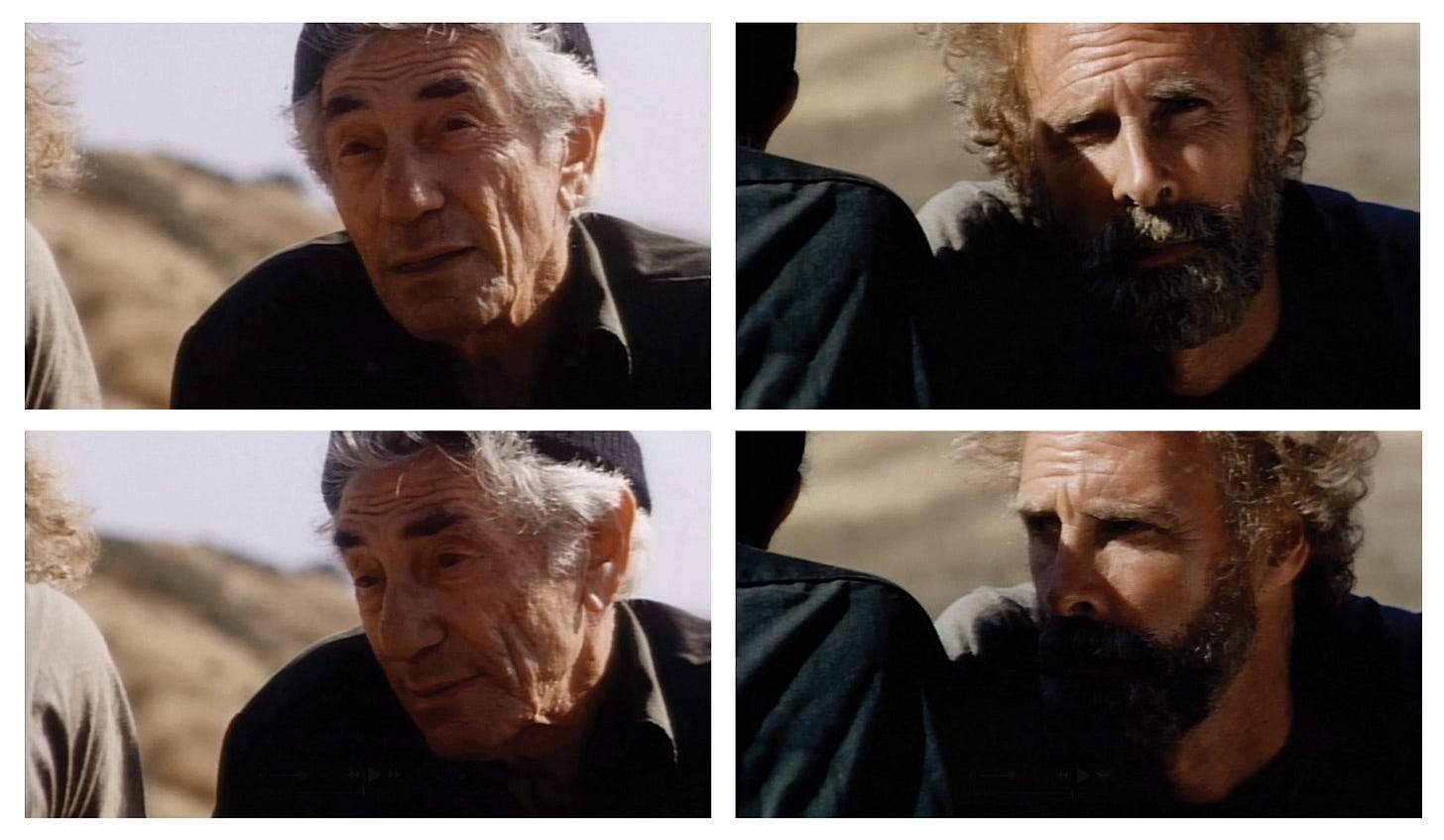

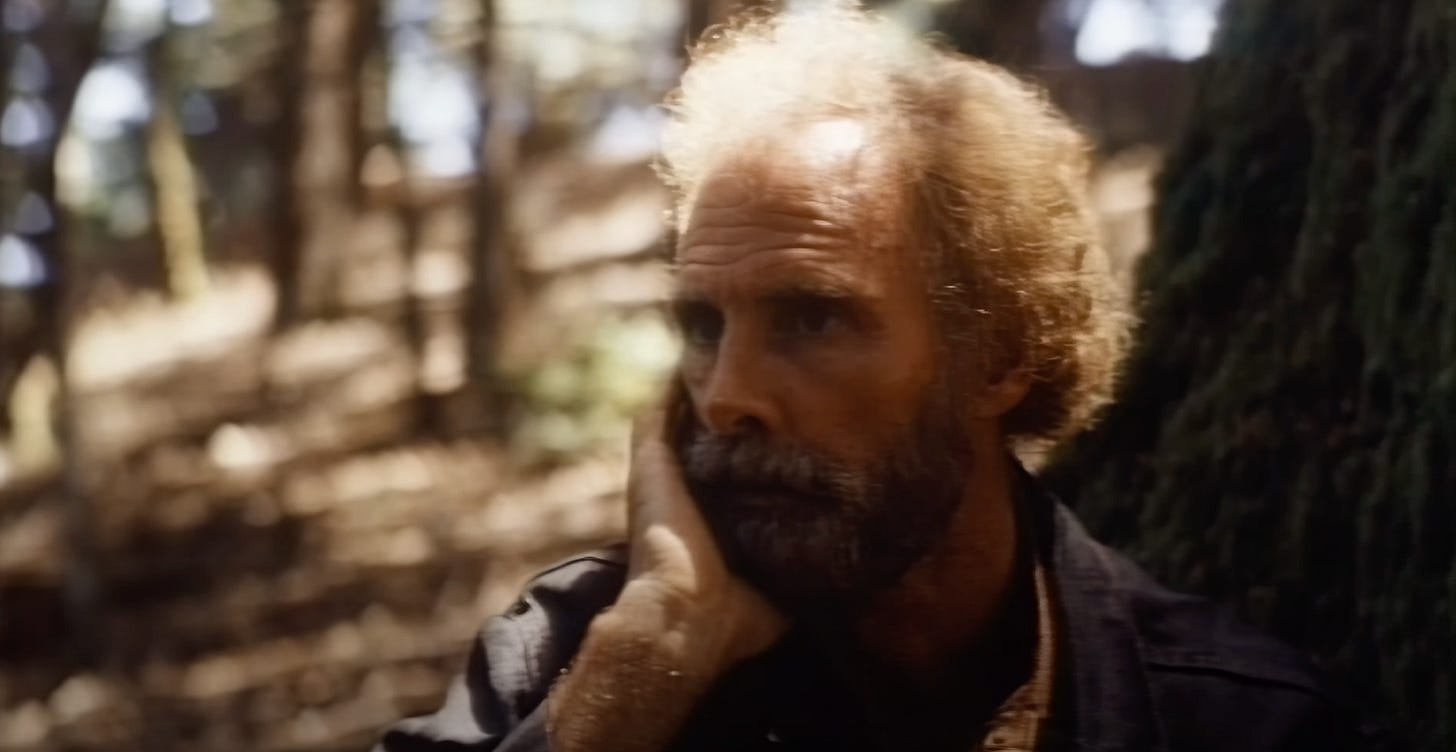

A middle-aged man (Bruce Dern) has just wandered into Marin County, silent as an Old West gunfighter. On his person: a small leather gym bag, the clothes on his back, and the sort of intense mien one expected from Dern, who was at the time primarily famous for playing rangy edge-cases. 1

The man exits a ferry and wanders through a junkyard toward Mt. Tamalpais. At the base of a tree, he uncovers the memorial plaque where he scattered his mother’s ashes decades earlier.

There’s a quiet moment. His sports watch beeps.

The man gets up to watch a bunch of runners wheeze by, climbing relentlessly uphill, competing in something called the Cielo-Sea Race. He takes notes on the winning times and hitches a ride back to town in a VW bus. It’s full of runners complaining about the new race director’s plans to monetize the Cielo-Sea.

They quickly figure out their new passenger, the mysterious man, is none other than Wes Holman — an Olympic-caliber 10k runner from 20 years earlier. And then one of them ruins the moment with an uncomfortable question: “You were banned, weren’t you?”

Wes politely asks to be let out on the side of the road.

What follows is what grabbed me.

Wes wanders into the brush, takes a long look at the top of Mt. Tam, strips down to shorts and shoes, and runs back up the damn mountain.

Suddenly, there it was: a golden-hour, long-distance shot of Wes ascending Mt. Tamalpais. He’s dwarfed by the landscape yet somehow also above the clouds, an inversion layer rolling in to drape the land and ocean below. It’s impossibly beautiful, pure sports cinema, the score an offbeat mix of an obsessive 17/8 electronic motif and pan flute. Shirtless, Wes crests the hill and whoops, hopping in a circle, his winged-track-shoe medallion jangling as he spins.

Even now, this scene makes me want to go trail-running the way “Pulp Fiction” makes me want to go to the long-gone Hawthorne Grill.

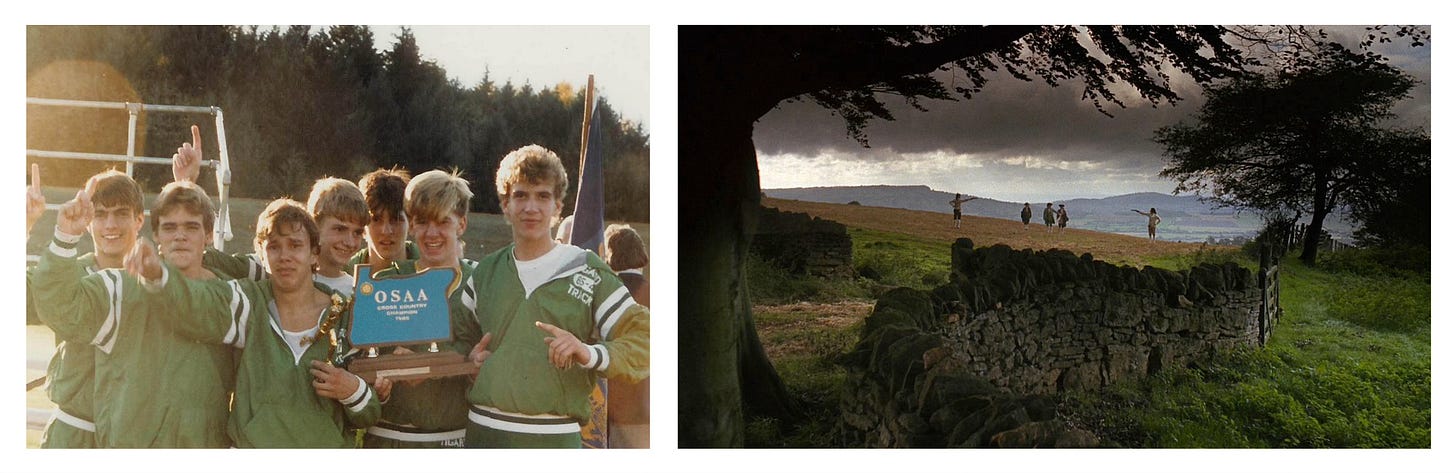

I was 16 when I saw this. My high-school long-distance coach had taken our team to a screening of writer/director Rob Nilsson’s “On the Edge,” at either The Movie House or KOIN Center Cinemas in Portland. It was May or June of 1986. We were basking in the afterglow of winning a state cross-country championship the previous November. And here, unspooling before us, was a movie made by and for runners. It told the story of 43-year-old Wes’s angry yearlong sabbatical, living rent-free on a half-sunken boat, while he trains to win next year’s Cielo-Sea Race as an act of personal redemption.

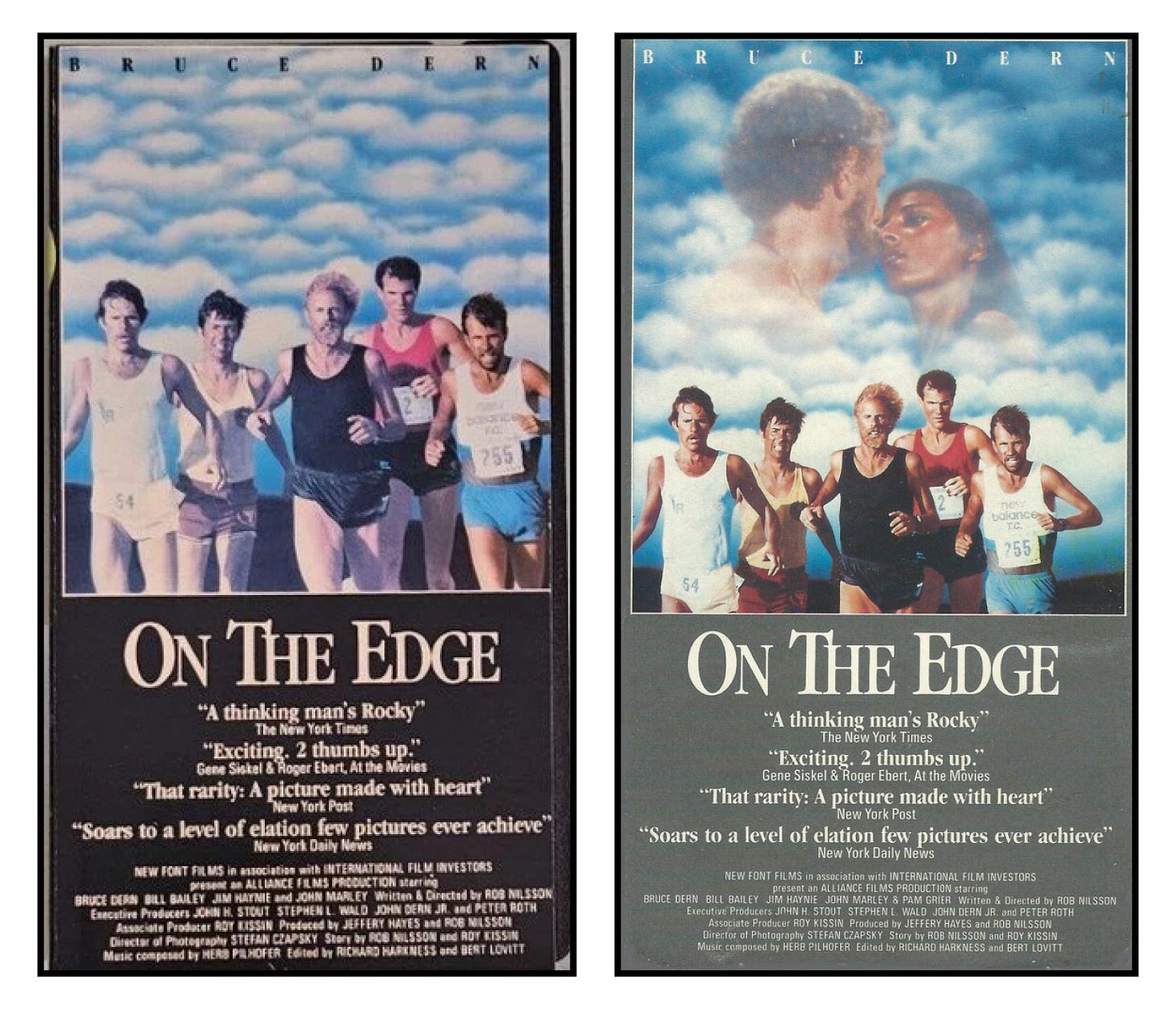

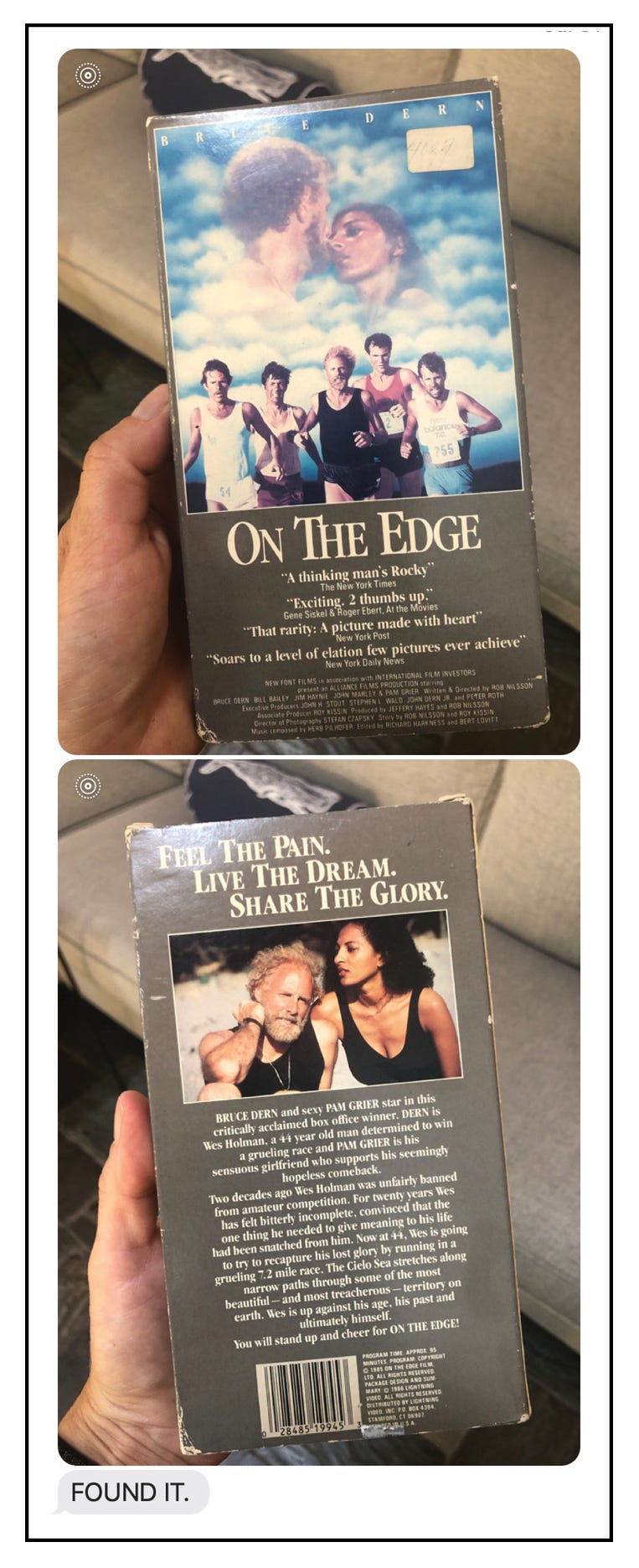

“On the Edge” had been reviewed as a “thinking man’s Rocky” by the New York Times. This did not translate into box-office dollars. My hypercompetitive teenage brain was caught off-guard by the ending — an ending I couldn’t fully appreciate at the time, but came to profoundly appreciate as my age caught up with Wes’. Nevertheless: In a tiny Portland movie house in 1986, the film crawled into my head and built a tiny shack there.

It’s hard to imagine today — in a video-saturated world where every midlist YouTube running influencer has their own camera crew and drone pilot — but this shot of Dern galloping up that golden grassy hillside was, in that pre-internet moment, a revelation. Running was rarely the centerpiece of a sports movie, much less running like this — as aesthetic experience, in nature, as capital-c cinema.

I was, by far, the biggest movie nerd on the team. I’m confident no one else reacted to this moment the way I did. I should also note I’m fully aware my reaction was (and is) outsized — it’s a beautifully lit and composed shot of a man running up a hill, not Barry Lyndon dueling at sunrise. But it was a perfect Venn-diagram intersection of my love of running and my love of movies, so it laser-etched itself onto my hippocampus.

Our team walked out of the theater with an in-joke — telling each other to “burn” and “soar” the way Wes’ coach tells him to “burn” and “soar” on the hills of Mt. Tam. I walked out with a desire to find and run trails. And I vowed to someday compete in the Dipsea Race, the real-world trail race that inspired the movie’s fictional “Cielo-Sea Race.”

At this point I turned 49.

I decided I’d better run the Dipsea while I still had some semblance of knees, and vowed to take a cue from Wes and spend a more-focused-than-usual year training for the race, albeit at a vastly smaller, slower, and less spartan scale. 2

Unfortunately, I made this decision in June 2019. The Dipsea was canceled and postponed by the pandemic for two-and-a-half years, the first time this historic race had skipped a year since WWII. The starting line, and my youth, stretched further and further away.

And so, like any runner having a bad day, I fell back on a secondary goal:

Learn as much as I could about the production of “On the Edge” — which remains out of print on physical media, was at the time unavailable to stream, and is in serious danger of becoming a lost film.

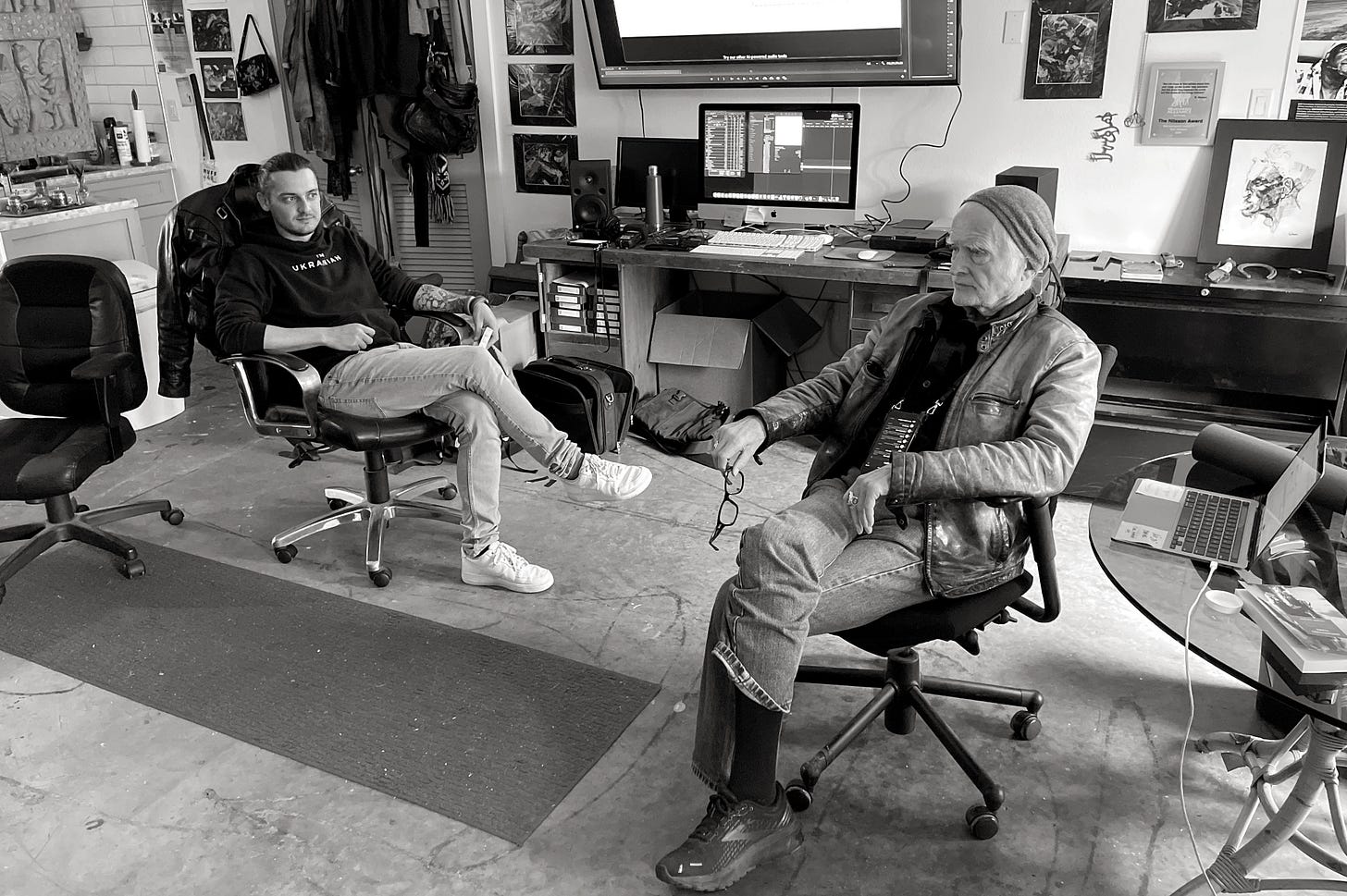

It started as a simple search of online newspaper archives. A few years later, I’d run the Dipsea Race (twice, poorly),3 cold-emailed several members of the production team, conducted a few Zoom interviews, answered the question “So why do you want to interview me about this?” an amusing number of times, driven to the Bay Area to meet Rob Nilsson (still making movies in his 80s), sat in a green room across from an understandably skeptical Pam Grier, and spent a few hours on the phone with Bruce Dern.

Today I can tell you that shot was likely filmed by second-unit cameraman Stephen Lighthill at the behest of Nilsson and cinematographer Stefan Czapsky in the late summer of 1983, after a drive up Ridgecrest Road, Dern having positioned himself 200 yards north of the crew on Bolinas Ridge, waiting for the light to be just so, having trained himself within an inch of his life at age 47 to help Nilsson realize his low-budget magnum opus on running and obsession and collective effort and father-son relationships and (depending on which cut of the film you’re watching) male-female relationships.

Here’s some other stuff I found out.

Tonally, “On the Edge” feels like a mid-’80s last stand of the subversive, class-conscious sports movies of the 1970s, where “losing with flair” counted as “winning” and “victory” was in the character development, or at least in the slobs-versus-snobs satisfaction of thumbing one’s nose at authority. 4

One particularly snarky Letterboxd reviewer dubbed its subgenre “jogsploitation,” which would place “On the Edge” squarely in the company of films like “Chariots of Fire,” “Personal Best,” “Running Brave,” “The Jericho Mile,” and those dueling Steve Prefontaine biopics from the late 1990s.

It’s also a solid entry in middle-aged-guy “one last ride” cinema. Wes Holman has returned to town with accounts to settle.

We learn Wes was banned from competition 20 years earlier for accepting under-the-table payments as an amateur. Back then, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) forbade Olympians from earning any sort of living wage from their athletic efforts. 5 This was a major issue for aspiring runners in the 1970s, one an impoverished Prefontaine famously railed against. Today it seems hopelessly quaint in an era where HOKA gives review shoes to “runfluencers” and college track stars announce their endorsement deals on TikTok.

In fact, much of the movie is quaint, and charmingly so — from its ’80s running fashions and forgotten shoe brands 6 to its characters openly fretting about big sponsors ruining the local character of the Cielo-Sea. 7

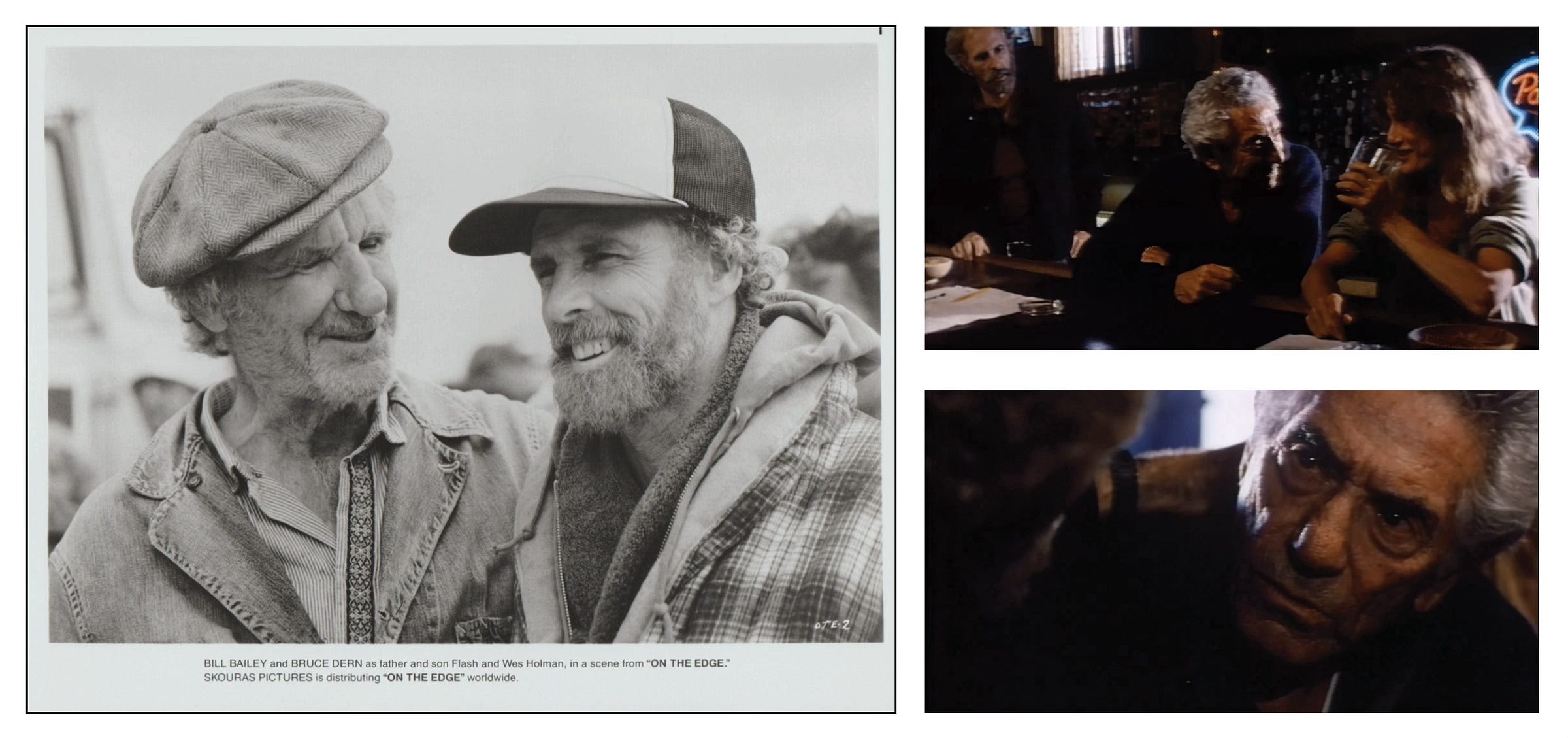

Wes heads to the 2 a.m. Club, an infamous Mill Valley bar you can still get sozzled in today. Inside he finds his former coach Elmo (John Marley, in his final performance). Declaring Wes “as persistent as a donkey’s fart,” Elmo reluctantly agrees to coach him one more time, on one condition: While he’s in town, Wes needs to reconnect with his father, Flash (Bill Bailey), an aging blue-collar radical trying to live off the grid in his Bay Area scrapyard. Flash has lost a step and needs his son.

“The age shift in this movie is interesting,” wrote Roger Ebert in his 1986 review of the film. “Instead of a kid with a father figure, Holman is a bitter, grown man who wants to prove something once again to the men who were so important to him years ago.” There’s also a flip in the usual political dynamic you see in movies with a generational divide: In this case, the son is struggling with a father who’s a dyed-in-the-wool leftist. Flash minimizes his son’s running career as “hyperventilatin’ all over the goddamn place” and declares sports “the biggest goddamn energy drain in this country.” Flash is also lost in his own “goddamn”-accented memories — heroic days of fighting union-busting scabs as a two-fisted longshoreman, alongside Wes’ mother, during “Bloody Thursday.”

One of my favorite moments in the film is a monologue my joints and tendons had to age into fully appreciating. Elmo, leaning on a fence after a long day scouting the Cielo-Sea course with Wes, remembers Wes’s blazing youth 20 years earlier — followed by a gentle knife-twist as Elmo poetically and somewhat floridly 8 reminds Wes that he needs to train a lot smarter in his 40s:

“There was a blast of late-afternoon sunlight that hit your hair, and you looked like you were running with pure yellow fire streaming behind you. And I remember thinking, ‘Christ, that’s youth right there’ — the damn sunbeams were right where you wanted them. [pause] That time is over now, Wes. You can’t get by anymore on balls and guts and three hours’ sleep, and you can’t count on the sunbeams, either.... Now I’d like to suggest a couple of things for your old age: Patience. Irony. You’ll live longer.”

There’s an amusing little beat when Elmo says “That time is over now, Wes.” For the first half of the monologue, Wes was in a reverie, dwelling on his glory days (not unlike his father) — but after the hairpin turn in Elmo’s speech, Wes turns to his coach with a mild WTF look on his face.

I brought this moment up to Nilsson during one of our interviews, but was a little glib in describing it as a purely comic beat. “It’s the punchline of this entire monologue,” I said, glibly. “A whole second monologue about how you now have to think and run completely differently, embracing patience and irony and training in middle age. We’re now going to teach you how to cheat on this course with the shortcuts.”

“Although that’s not how he would’ve put it,” Nilsson replied. (Shortcuts are actually not considered cheating in the Cielo-Sea, or the Dipsea Race.)

“No, no. I’m paraphrasing.”

“I know you’re paraphrasing. But Elmo was a true believer. For him it was almost the religion of running, and he was dead serious about it. Not that he didn’t have some irony in there.... I wanted to make that point that [Elmo] saw deeper than anyone else what it was about, if he wanted to do it right. If he didn’t want to do it right? It didn’t matter. You can go ahead and have a good time, and maybe some natural talents will get you pretty close. But the great ones are completely fixated on ... the three things we discussed: philosophy, strategy and training.”

“One of the things Elmo tells him all the time is ‘You’re training too hard.’ You’re training like a young man, essentially.”

“There’s also that. Yeah. You’ll have to try too hard and you have to ease up at the same time. There’s a paradox in that.”

Wes runs afoul of the Cielo-Sea’s new race director, Owen Riley (Jim Haynie). In a Greek-tragedy level of coincidence, Owen turns out to be the roommate who ratted Wes out and got him banned 20 years earlier. Owen is bureaucracy in human form — a sweaty, pompous dork who unironically says stuff like “The system works for the man who pulls his oar.”

Now, still citing AAU-style regulations, Owen refuses to let Wes enter his race. 9

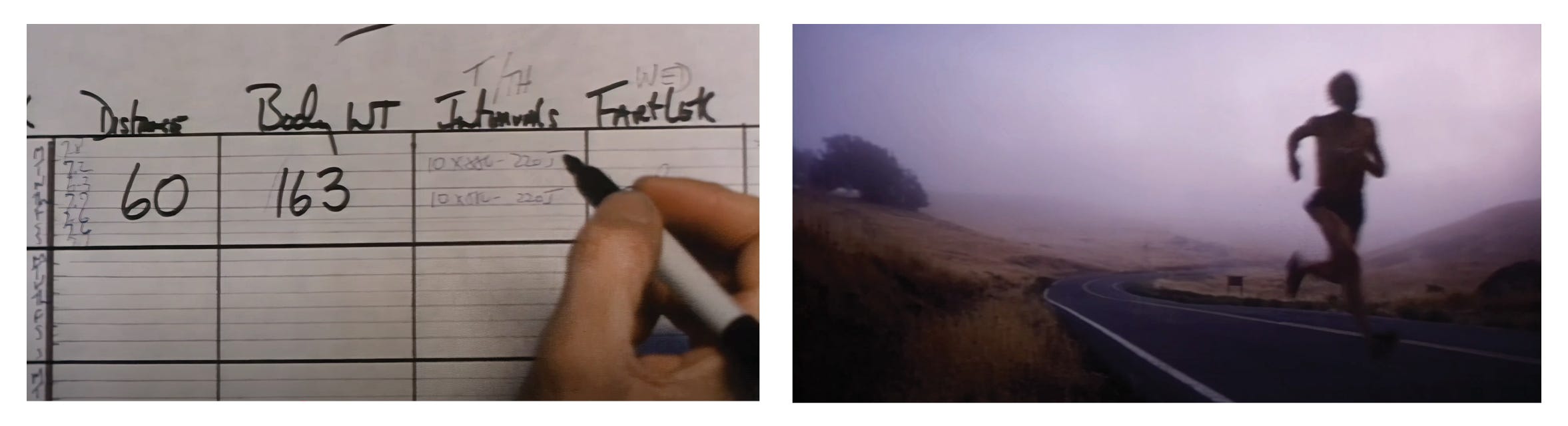

The film’s first hour is Wes struggling through his year of overly intense training. And it’s realistic training. This is the only running movie I’ve ever seen where the protagonist pins to his wall a handwritten quarterly training schedule listing weekly mileage, featuring words like “intervals” and “fartlek.” And unlike any running movie I’ve seen before or since, “On the Edge” captured the actual feeling of training and recovery. It understood the beauty of striding along grooves of dirt that cut geometrically across shoe-ad-perfect grassy plains. But it also understood that training can be lung-burningly shitty and boring. Wes spends a fair amount of the film’s runtime grinding out miles in bad weather, soaking in a tub set up in his half-sunken boat, 10 and nursing the odd charley horse. I was personally tormented by the lung-burn in high school and spent a decent chunk of my waking life dreading the discomfort of racing, so I appreciated the movie’s honesty, even if seeing it onscreen in 1986 left me twitching with sympathetic anxiety.

Wes also struggles to interpret Elmo’s advice that he needs to become an “artist” as a runner in middle age. This leads to the scene my teammates loved ironically quoting during workouts. Elmo issues a final training challenge to Wes, a reverse-psychology exercise (filmed, again, on that golden Mt. Tam ridge). “I want you to go out and feel the course,” Elmo tells Wes. “Burn the uphill and soar the downhill. But when you burn, you say ‘soar,’ and when you soar, you say ‘burn.’”

More irony. More paradox.

All these threads come together an hour in, when Wes takes a revolutionary page from his father and decides to enter the Cielo-Sea as an unregistered “bandit.” It’s here the movie becomes its best self, and also its silliest self. Nilsson lets a bit of slapstick enter the picture as Wes becomes a local folk hero over the course of the race as it’s happening, inspiring spectators to the point of riot. This happens thanks to live local TV coverage. 11 It also happens thanks to the actions of some sympathetic professional runners —many of them the same ones who picked Wes up in that VW bus — as they band together to keep Owen and his race officials from tackling Wes and yanking him off on the course.

Runners start knocking race officials into ponds. The frenzied crowd knocks over tables of Styrofoam Dixie cups. They throw the timing clock into the ocean. It’s gleefully anarchic and more than a little ridiculous.

I love it, and here’s why:

Most running movies, even the good ones, tend to devote limited screen time to the actual “running” part because they can’t figure out how to make racing in circles terribly interesting. 12 Ball sports tend to be more cinematic — and make for more popular movies — because they have movie stuff: props, MacGuffins, rules, visual goals, not to mention an entire cast of players, support staff, and spectators performing distinct but dramatically interconnecting roles. Even a great running movie like “Without Limits” focuses more on Pre’s outsize personality and his relationship with his coach.

Not so here. The final half-hour of “On the Edge” is an epic set-piece devoted entirely to the running of the 73rd Annual Cielo-Sea Race. It’s as big as the modest $1.6 million budget could possibly allow, complete with helicopter shots of Wes summiting various hilltops that play like “Lord of the Rings” in singlets and short-shorts.

Wes’ superiority during the race is never really in doubt. We just spent the last hour watching him train harder than anyone else, after all, and the Cielo-Sea’s handicapping system puts him on the course ahead of younger male runners in their prime. The frisson comes instead from attempts to stop him, the spectacular landscapes, and Wes’ growing folk-hero status, accompanied by his growing realization that he’ll only finish the Cielo-Sea if he works with the hastily assembled army of fellow racers surrounding and protecting him.

This leads to the film’s finish-line ending, which I won’t explicitly spoil here. Suffice to say a simple but powerful gesture makes it clear Wes has learned a key lesson over the last year, much of it over the last 30 minutes: Nobody does it alone.

“They throw the clock in the ocean because time doesn’t mean shit — relationships do,” Dern, then 87, told me during an epic phone call. “There are several points in the movie where you see Wes encompass more things into his life, in his journey of trying to make up with his dad.”

“On the Edge” contains one of Dern’s finest performances, even if you include his late-career rediscovery at the hands of Tarantino and Alexander Payne. It’s a performance peppered with gentle and quiet moments that teenage me certainly wasn’t expecting from him in 1986. The movie also makes trail-running look incredible, thanks to a murderer’s row of talent behind the camera that includes future Tim Burton cinematographer Stefan Czapsky, future American Society of Cinematographers president Stephen Lighthill, and Paul Ryan, who shot second unit on Terrence Malick’s “Days of Heaven.” And I have a movie-music-nerd’s love for Herb Pilhofer’s eccentric score, especially when Pilhofer samples his own 1976 jazz/flamenco composition “101 in the Shade” as Wes rolls down the mountain with his huffing band of competitors-turned-defenders. 13

There may be “better” running movies, sure. (“Without Limits” is almost certainly a “better” running movie, and Nilsson himself lists the 1960s British kitchen-sink drama “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner” as a personal favorite, with themes of class rebellion that clearly influenced “On the Edge.”) But this scrappy, personal, deeply felt little indie is by far my favorite movie about the sport, the one I turn to again and again to get pumped before race day. I’ll take its goofy rebel energy over the stately greys of “Chariots of Fire” any day.

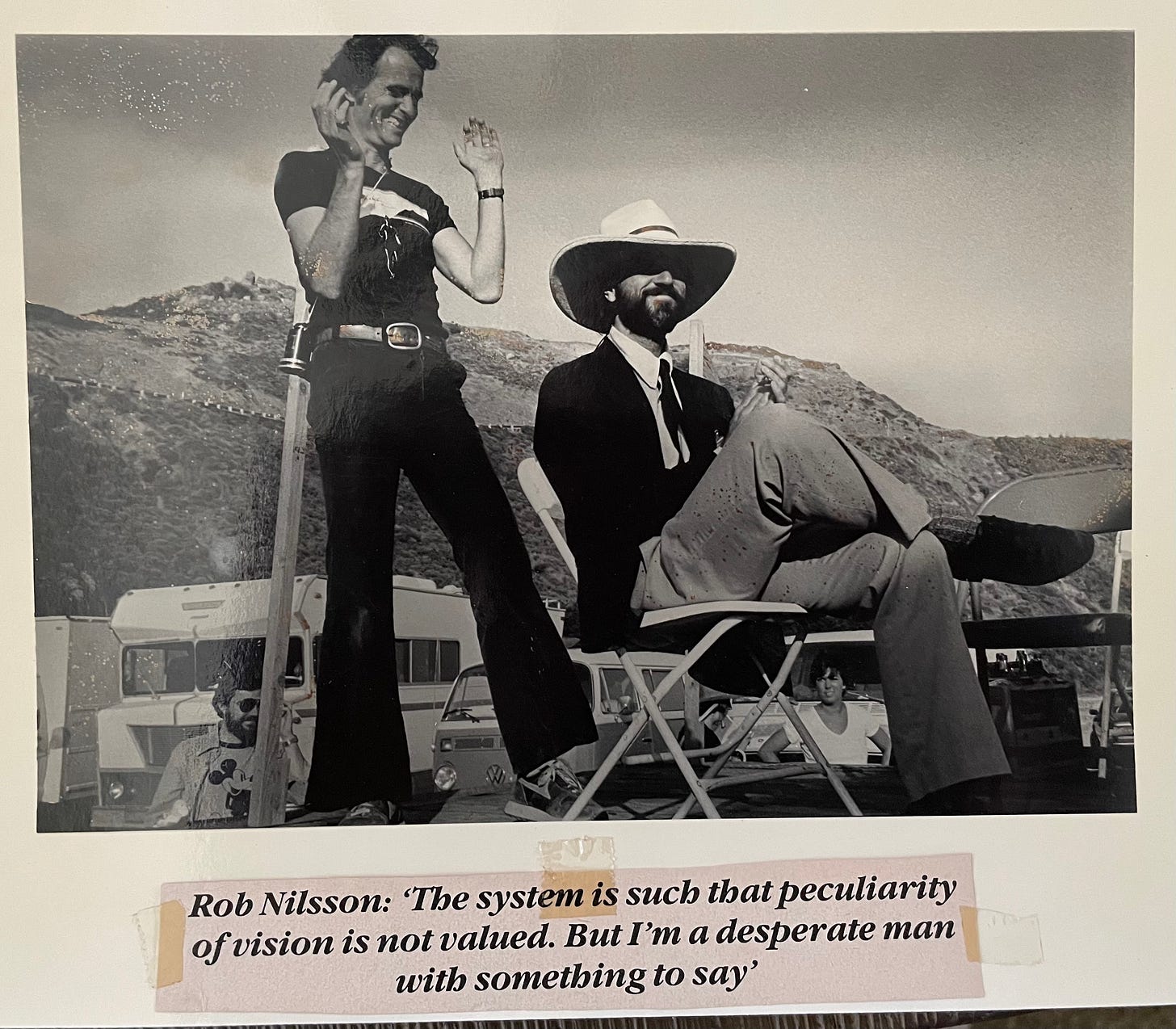

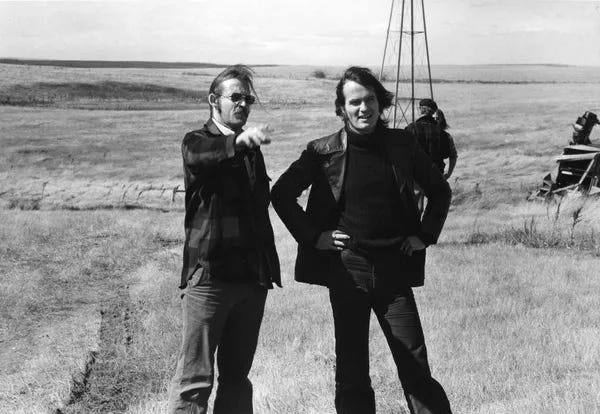

Rob Nilsson began gathering ideas for “On the Edge,” originally titled “Of the Crater,” around 1975, when he was a member of the Cine Manifest collective in San Francisco. This small group of filmmakers (Nilsson, John Hanson, Stephen Lighthill, Steve Wax, Peter Gessner, Gene Corr, and Judy Irola) worked out of a building on Folsom and 11th that also housed a leather bar. They espoused Marxist ideals and pooled their incomes toward a shared goal: making movies centering on the lives of working-class people. 14

Then 36, Nilsson’s road to Cine Manifest had been a winding one. Born in Rhinelander, Wisconsin, the grandson of early-1900s documentarian/photographer Frithjof Holmboe, he’d done time as a Harvard student, mess boy on Swedish freighters, civil-rights activist in Mississippi, Peace Corps volunteer in Nigeria, poet, painter, teacher, and Boston cabbie. 15 The New York Times once described him as looking like “a sinewy cross between Chet Baker and Clint Eastwood,” a description that still echoed when he walked into a Berkeley restaurant wearing a beat-up leather jacket to meet me in 2023. He was 83, his runner’s knees pounded into chalk and replaced several years earlier, but his persuasive charisma was very much intact. Talking with him for any amount of time leaves you wanting to don a beret, aid his cause, and carry a standard, or at least a boom-mic. I’m not surprised many of his artistic collaborators have worked with him for decades.

He’d fallen in love with filmmaking thanks in part to a revelatory 1960 screening of John Cassavetes’ first feature, “Shadows,” at Manhattan’s Bleecker Street Cinema. In his book of essays and criticism, Wild Surmise, Nilsson writes that Cassavetes’ film made him realize movies “can be about the ‘you’s and I’s’ of this world.”

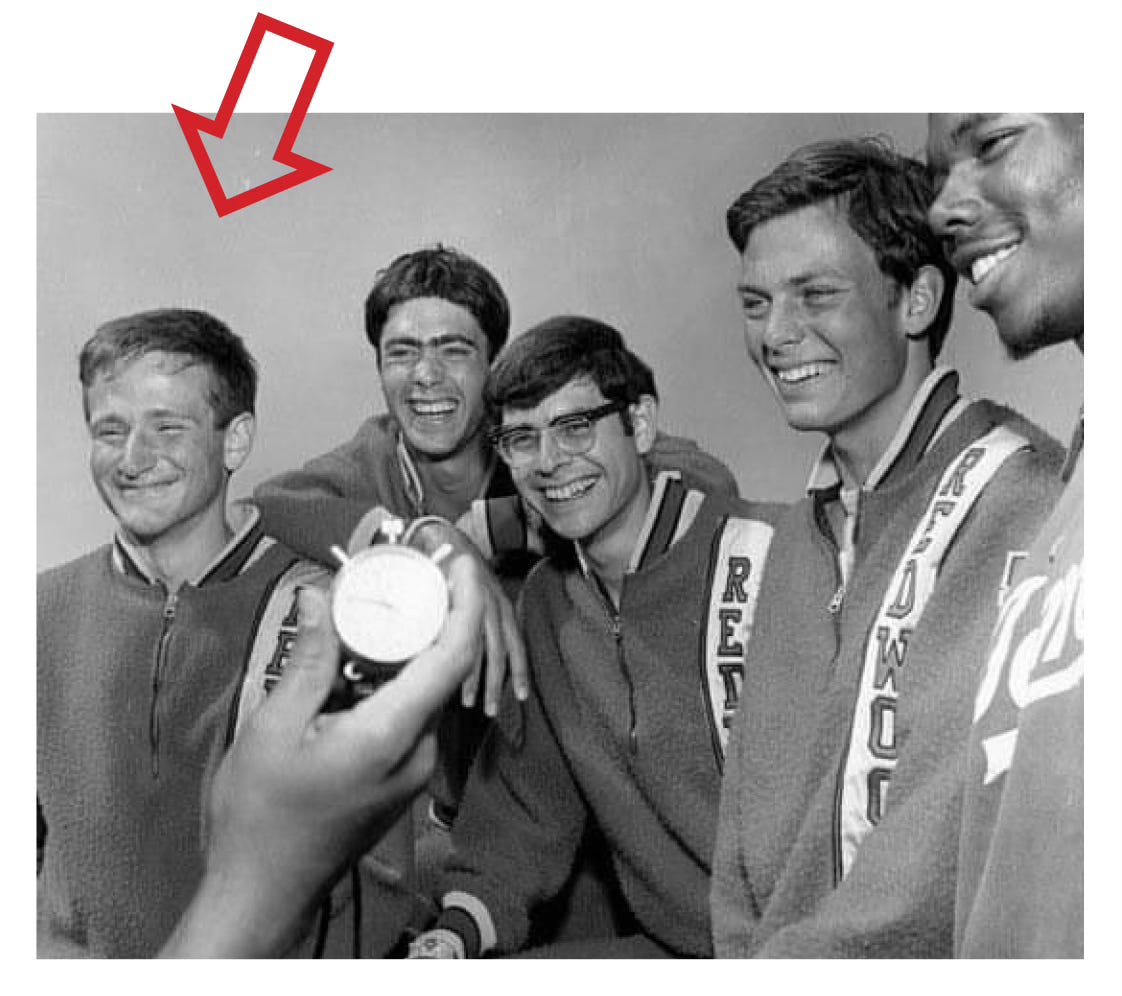

Nilsson was also a lifelong runner. He recalls getting the bug at age 11 or 12, at Camp Tesomas in Wisconsin, while running down a sandy tree-lined road in pursuit of a Boy Scout athletics merit badge. He had some talent. By the time he graduated from Tamalpais High in Mill Valley, California, he was first man on the cross-country team, and had already run the local Dipsea Race at the urging of the previous year’s team captain, Wes Hildreth. (Hildreth would go on to become Wes Holman’s namesake, as well as a respected volcanologist. He was killed in a car accident in Nevada in June 2025, just six days after his induction into the Dipsea Race Hall of Fame. He was 86.) 16

“To me, running is the supreme human sport,” Nilsson told me. “There’s nothing that’s more primordial, I think, than a sport based on your survival in times when you had to run like hell to get away from the tiger or whatever else. There’s a kind of painful grandeur in it.... I suppose to the extent that you’re running away from things as well as running towards them, it represents both your boldness and your cowardice, writ large.” “On the Edge” glories in shots of the human body, in toned legs and arms straining to create locomotion.

Nilsson competed on Harvard’s cross-country team until, as he put it, “I decided I was a poet and whatever else and took to the more boho pursuits in life.” He returned to running when he returned to the Bay Area, joining the local Tamalpa Runners club and competing in 10ks, marathons, and multiple Dipsea Races until his knees finally gave out in his 60s. (“Wish I could run it again,” he once told me over email. “Walking is boring.”) Early drafts of the “On the Edge” screenplay feature a cover photo of a young Nilsson in shorts and a tank-top, striding through the grass of Mt. Tam, a hillside rising behind him.

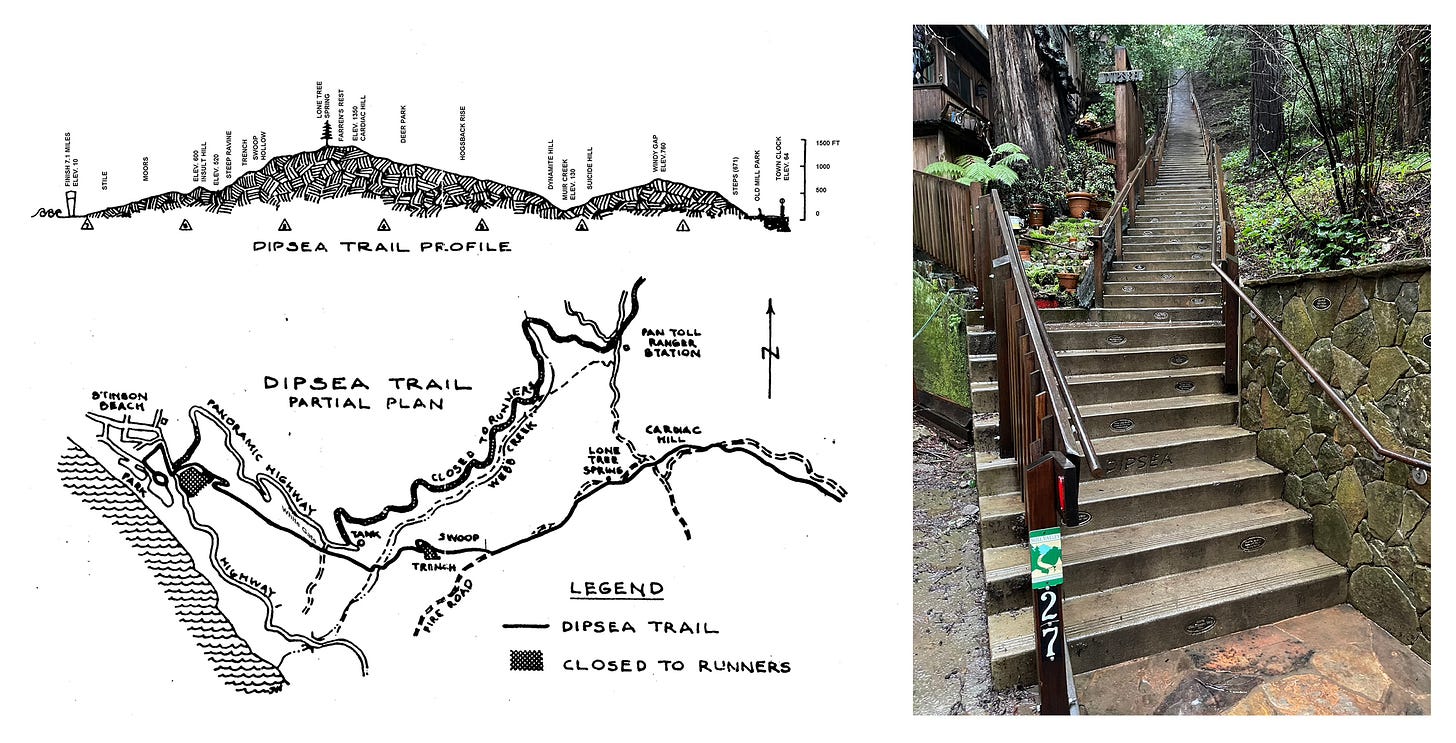

The Dipsea Race is an essay all its own (as is my comical, ever-lengthening attempt to get fit enough to survive it), but the short version is that it’s not surprising Nilsson thought it could serve as the foundation for a movie. It’s a course that begs to be photographed.

A race over a small mountain in Marin County, California, the Dipsea is America’s oldest trail race, and America’s second-oldest footrace behind the Boston Marathon. It was first run on a bet I like to imagine was drunken in 1904, formally launched as a race in 1905, and run for the 114th time in June 2025.

It’s a beautiful, quad-busting cardio nightmare of a course. You start in downtown Mill Valley. Almost immediately, you find yourself running up nearly 700 stairs, in three flights, a 500-foot elevation gain over a third of a mile. These are collectively known as “The Dipsea Steps,” and they’re pretty much the worst start to a footrace I can imagine. Then, after a short downhill, you keep running (or, if you’re a normie like me, power-hiking) up, over Mt. Tamalpais, until you bomb back downhill to Stinson Beach. Part of the descent is on stairs so twisty and eroded they become a corkscrew fever-dream of tripping hazards. It’s about seven-and-a-half miles total and feels like 15, with about 2,200 feet of total elevation gain. The race has distinct and frequently breathtaking segments that feel like chapters in a saga, with names like “Cardiac,” “Dynamite,” “The Swoop,” “Steep Ravine,” and “The Moors.”

It’s a race proud of its eccentricities. Shortcuts are allowed. You can only register by snail-mail for one of its 1,500 racer slots, which keeps the Dipsea, despite its rich history, feeling about as hyperlocal as your average suburban 5k. And the race is handicapped — with older, younger, and slower runners getting varying degrees of head start. This means anyone can theoretically win the Dipsea.

A 72-year-old won it in 2012. An 8-year-old won it in 2010.

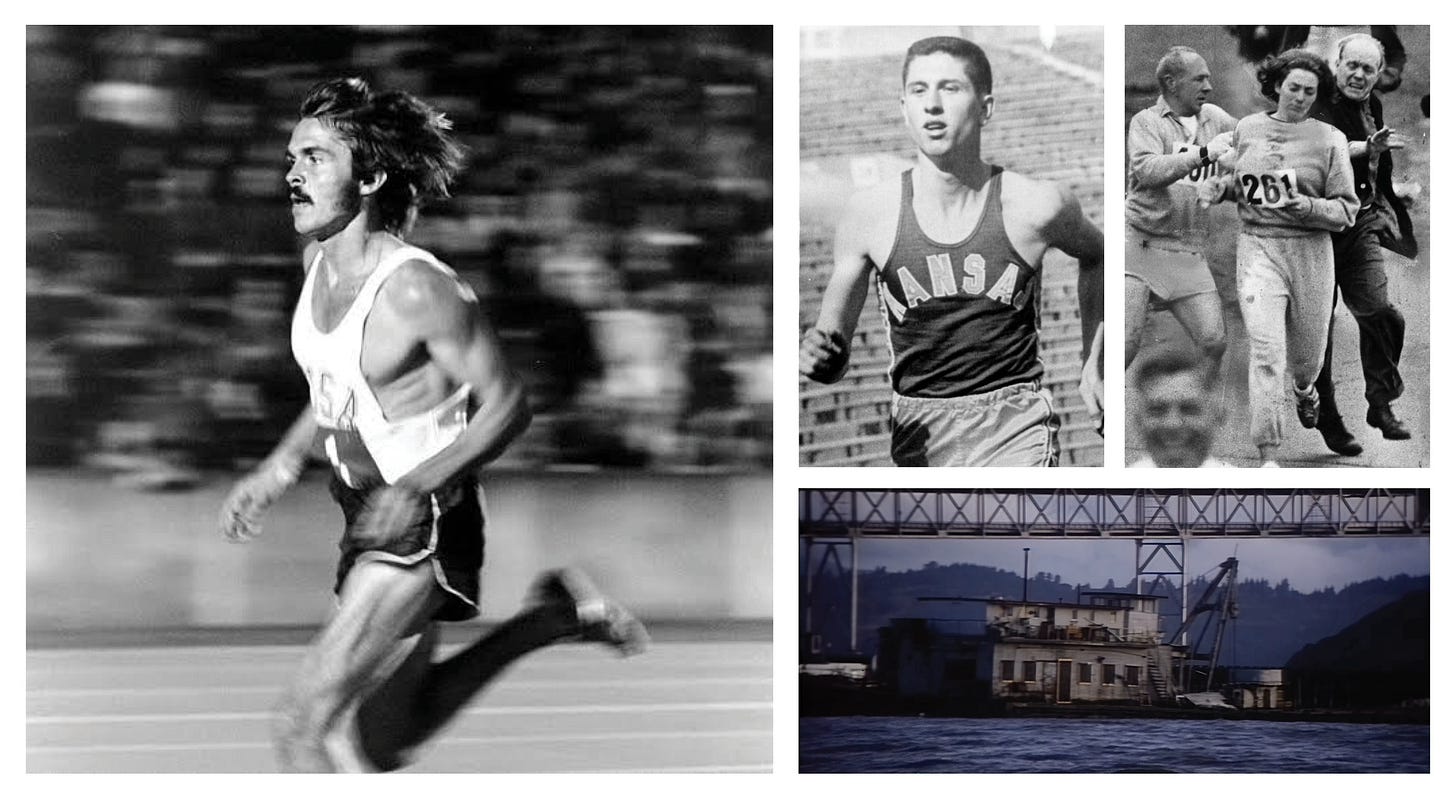

In addition to drawing heavily from his own personal relationship with running and the Dipsea, Nilsson drew from sports headlines: Prefontaine’s iconoclastic cool and his battles with the AAU; the 1980s disappearance (and re-appearance) of distance prodigy Gerry Lindgren; miler Wes Santee’s 1956 ban from amateur competition; and race official Jock Semple’s attempts to yank Kathrine Switzer off the Boston Marathon course in 1967.

In fact, many of the elements in the film that seem a little over-the-top are based on real information. Race officials trying to tackle Wes? Semple tried to do the exact same thing to Switzer. That sunken clam-dredger Wes lives in during his training? It was a real location, and people did, in fact, squat there. “Every year I’d drive by and see it sunk a little further,” said “On the Edge” co-writer/producer/actor Roy Kissin. “Now it’s gone.”

By the end of the 1970s, Nilsson had an initial draft of “On the Edge.” It dovetailed nicely with his indie-filmmaker breakthrough. Working with a small crew of Cine Manifest comrades, Nilsson had just co-directed “Northern Lights,” a black-and-white 1978 film about North Dakota farmers organizing in 1915 to fight bank, railroad and grain monopolies. In 1979, it won the Camera d’Or at Cannes. This was the moment! He and “Northern Lights” co-director John Hanson formed a production company, New Front Films, each hoping to make their own personal movies. 17

Then a brutal fundraising process began. Wes’ fictional long-distance project took a year out of his life. Nilsson’s would take half a decade.

“On the Edge” resonates as a running movie the way it does largely because of two key people who joined the production: Bruce Dern and Roy Kissin.

Kissin, a 10,000-meter All-American for Stanford and two-time Olympic Trials competitor, was deeply embedded in the running scene. Fresh out of Stanford, living in San Francisco, he also wanted to get into movies.

And then a gold bar dropped out of the sky.

“I read this little blurb in CitySports that Rob wanted to make this movie based on the Dipsea,” Kissin told me in 2021. “I knew his film ‘Northern Lights,’ which was quite an impressive accomplishment, so I just called him up and introduced myself... I think Rob saw an opportunity to leverage my knowledge of the sport and make the running aspect of the film kind of resonate and be true — and leverage my social profile in the running world to help get the movie made. For me, it was just perfect: I know about running and I want to be in film and this is a film about running.”

Kissin had worked as a production assistant on a few films, “and from that experience I kind of sized up pretty quickly that really there are sort of three interesting jobs on a film set. Director, obviously. Well, how do you do that? How do you become a cinematographer? Well, I’m not sure how to do that. But you want to become a producer? Poof — you’re a producer. It turned out that I was not terrible at fundraising.”

Kissin would also earn a cowriter credit as he and Nilsson shaped the story. “My writing role was somewhat limited — the script was all Rob’s,” he recalled. “We’d sit for hours and hours with all the scenes mapped on 3x5 index cards. That’s where I gave the most input, plus scene-specific comments on coaching or training — stuff Elmo or Wes might say.”

Kissin served as Nilsson’s social gateway into the larger running scene. “We even once went to Colorado and ran briefly with [1972 Olympic marathon gold medalist] Frank Shorter, and Shorter gave us some of his running gear,” Nilsson told me. “That was Roy. How else could I have had the access to it?” 18

Kissin ran the Dipsea Race for research in 1982, while he and Nilsson were still prepping and fundraising. Kissin ran the fastest time that year, but placed 11th because of the race’s handicap system. He returned to running in his 40s, and today holds the record for the most years between top-35 Dipsea finishes. He ran his final Dipsea in 2018 at age 61, placing 25th.

“He could have been an actor — he’s a good-looking kid,” Dern remembered of Kissin when we talked in 2023. 19 “He was learning to be a producer on that movie. So he was half-gofer, half-whatever. And he never questioned anything that Rob would tell him to do in front of anybody else. I liked that.”

The casting of Dern was the real coup. A hybrid of character actor and leading man, with a congenital allergy to bullshit, Dern captured Holman’s intensity, drive, and obsessiveness — because even a casual scan of his “On the Edge” press clippings (and mine was the opposite of casual) reveals he actually is that guy.

Dern got involved through his lawyer brother John “Jack” Dern Jr., who knew Nilsson’s longtime lawyer John Stout. Nilsson apparently considered Kris Kristofferson and Sam Shepard 20 for the lead as well, but it’s hard to imagine another actor embodying the part of Wes Holman to the degree Dern does, or working as hard to realize it.

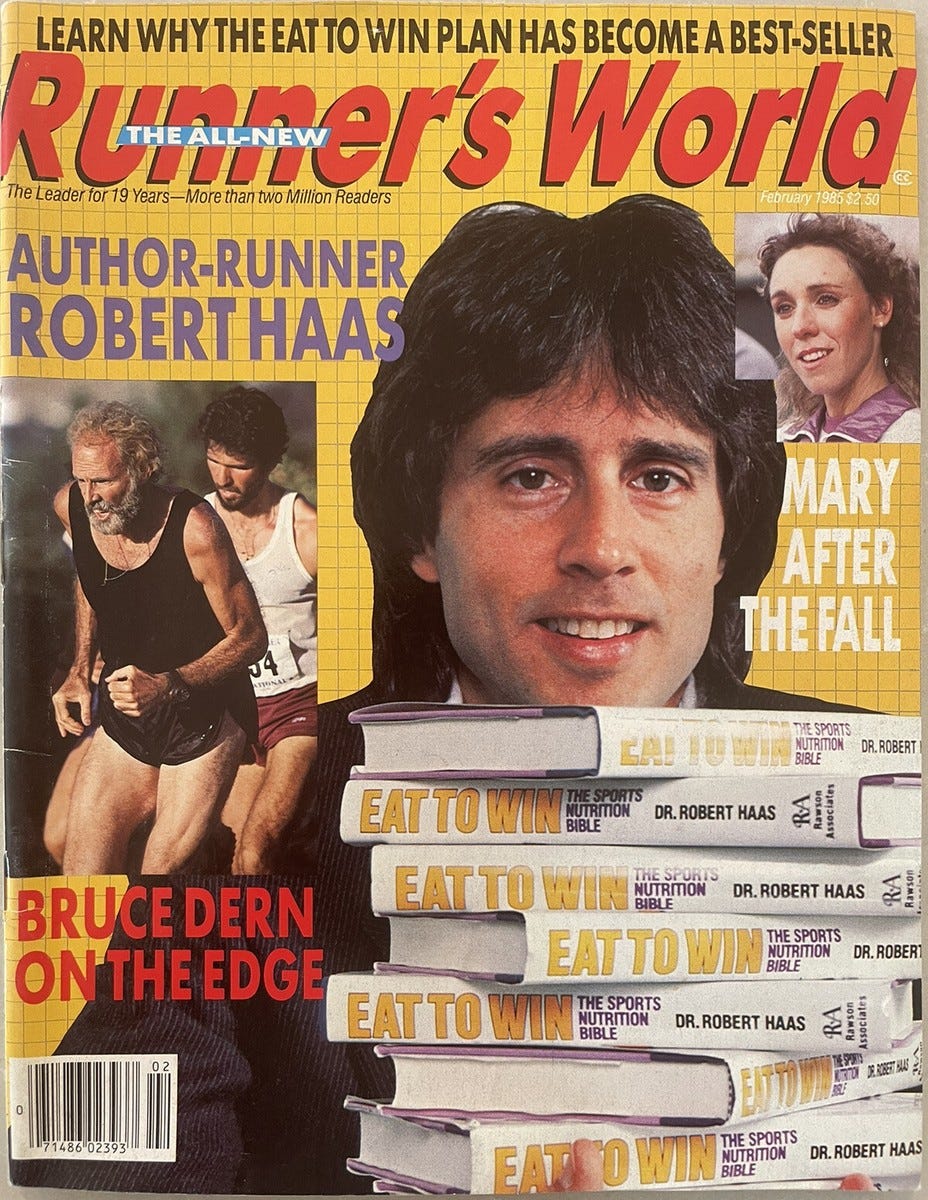

First off, Dern was an actual real-deal runner and evangelist for the sport. Like Nilsson, he’d caught the running bug as a kid at summer camp. He grew up to become a University of Pennsylvania 880-yard star, but quit the team in 1956 because he refused to shave his sideburns. He then became a pioneering ultrarunner in the 1960s, competed in the Senior Olympics in the 1970s, and during the “On the Edge” press tour estimated he’d logged 100,000 miles — four complete circumnavigations of the earth — since childhood. In one of his many Runner’s World cover stories, Dern bragged that he once held an unbroken 17-year run streak. In 1982, the year before shooting “On the Edge,” he hosted a documentary about the Ironman Triathlon where he ran during his “walk-and-talk” segments. He met Prefontaine in Eugene, while filming “Drive, He Said” there in 1970.

He’d also run the Dipsea Race, though he may have been slightly tricked into doing so. In 1974, Dern was shooting “Smile” for director Michael Ritchie, who lived on Mt. Tamalpais. According to a 1986 article in the San Francisco Chronicle, Ritchie told Dern, “We have this little race that we run every year. I’m not going to run it but I watch it; it goes right by my house. Why don’t you run it?”

“So I entered that morning,” Dern told me a half-century later. “They said, ‘The course is a snap. Once you get out of Mill Valley, it’s just the path.’ And I said, ‘Okay’ — not knowing that Mill Valley was 912 fucking steps.” He finished 293rd. During the 1986 “On the Edge” press tour, he described the race as the “grimmest running experience of my life in terms of risk,” “absolutely suicidal,” and “one of the most hair-raising experiences I’ve ever been through.” 21 Nevertheless, he met with Nilsson as the fundraising odyssey began.

“I went to Dern’s house in Malibu, on the beach, to pitch the film,” Nilsson recalled. “He said his only misgiving is that he was only doing this” — a running movie — “the one time. His thing was, you give out some emotional part of yourself and you never get that back. That’s what he believed. He was saving parts of himself for the running movie he’d want to make.”

“First of all, a guy gives me a script where the lead’s name is ‘Wes Holman,’” Dern remembered. “Now, just that alone, I look at that, first thing I see on the first page is Wes ‘Whole Man.’ Well, he’s trying to make a movie about whole people. And if you put them in a collective, the whole collective wants to finish. They don’t care what time it is — they want to finish. And that’s kind of Rob’s spirit.”

I drove through a nasty wall of weather to the Bay Area to interview Nilsson in 2023. To my great relief, he seemed amused rather than alarmed by my interest, and he let me borrow a stack of five separate drafts of the “On the Edge” screenplay. As I drove over the Richmond Bridge back to my Mill Valley Airbnb, the scripts in a bag in the trunk, it felt like the atmospheric river might blow me off the top deck of the bridge like a leaf, spiraling me gently into San Francisco Bay, my questions and long-sought answers lost in the same waves.

I scanned in all 665 screenplay pages with my phone over the next couple of days. The earliest drafts feature variations on a classic ’70s antihero ending.

In the first and several subsequent drafts, Wes wins the Cielo-Sea, only to wake up and realize his feverish victory was a hallucination — race officials had, in fact, successfully tackled Wes and pulled him off the course, knocking him unconscious. Those drafts end with him clambering to his feet and slowly running off into the woods, alone, in the opposite direction of the remaining middle-of-the-pack racers climbing uphill.

The ending was a provocation — serving up a traditionally happy sports-movie denouement, then confronting the audience with the artifice.

It wasn’t Dern’s bag.

“We didn’t shoot that,” said Nilsson. “The deal I made with Bruce was the film that you saw, in terms of the ending” — the runners working together, so everyone, including Wes, finishes as one. “I don’t think he would have wanted to do a film where, in the end, he kind of walks off alone. And I wanted to work with him, because he was the one actor.”

The ending I saw in the theater is still subversive, what with all the shoving race officials into ponds and throwing timing clocks into oceans, but it’s also joyful — a riot as celebration. While Nilsson admitted to feeling a bit “existential” about the ending change, he also told me he can find it in himself to appreciate it as a “big, Frank Capra style gambit — Herb’s music building it up to a Capraesque ending I’ve looked at many times. And I have to say, in spite of my Cassavetian druthers, I get touched by it, by a certain innocence or affirmation about it. It might be a bit corny. I don’t care.”

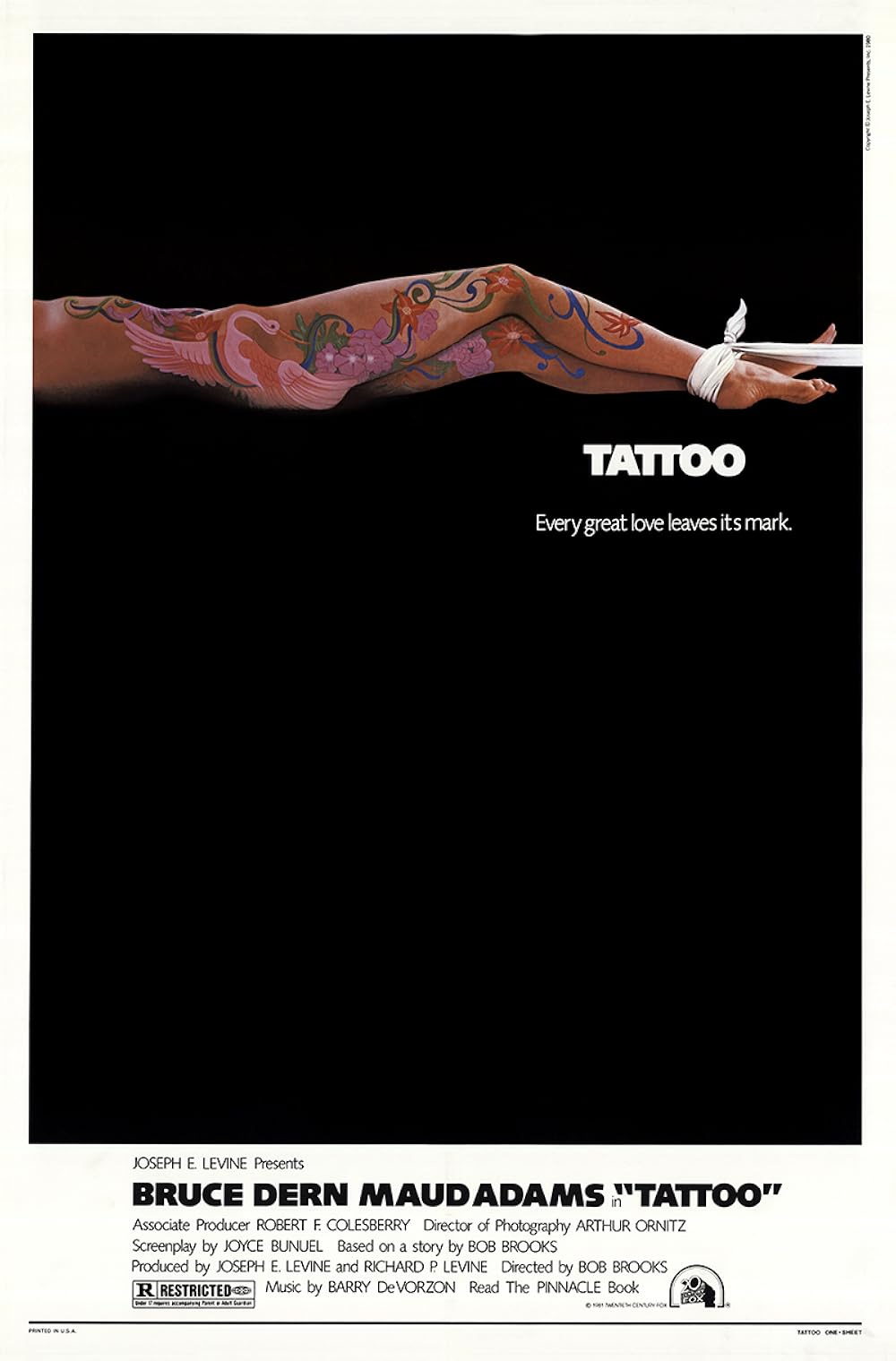

The differences between script and screen didn’t end there. The closest to a shooting draft featured a complete relationship arc I never saw in a theater.

In it, Wes has a girlfriend. Sort of.

On the airliner taking him to the Bay Area, Wes is seated next to Cora Melville, a dance-exercise instructor in an open relationship. Between Wes’ bouts of increasingly obsessive training, they embark on an increasingly obsessive series of hookups — explicit sex scenes ranging from gentle to table-flipping in a variety of locations. Wes shares his backstory with Cora. We learn he’s not simply “on sabbatical,” as he tells Elmo in the final film — he’s a divorcee who lost his coaching job because he pushed his athletes so hard they quit. Cora challenges Wes’s anger and single-mindedness, urging him to lighten up and spiritually “dance.” She echoes Coach Elmo’s advice to stop running with “too much form” and become “an artist.”

“It was about obsession,” said Nilsson. “Wes Holman was an obsessed character and his obsession was running, but in a love affair, he would have the same intensity.” In her final scene, Cora breaks it off for good, leaving Wes standing alone in Steinhart Aquarium, images of captive sea life serving as a visual motif throughout their torrid affair. Dramatically, it’s a final straw, cementing Wes’ realization that he really does need to loosen the hell up.

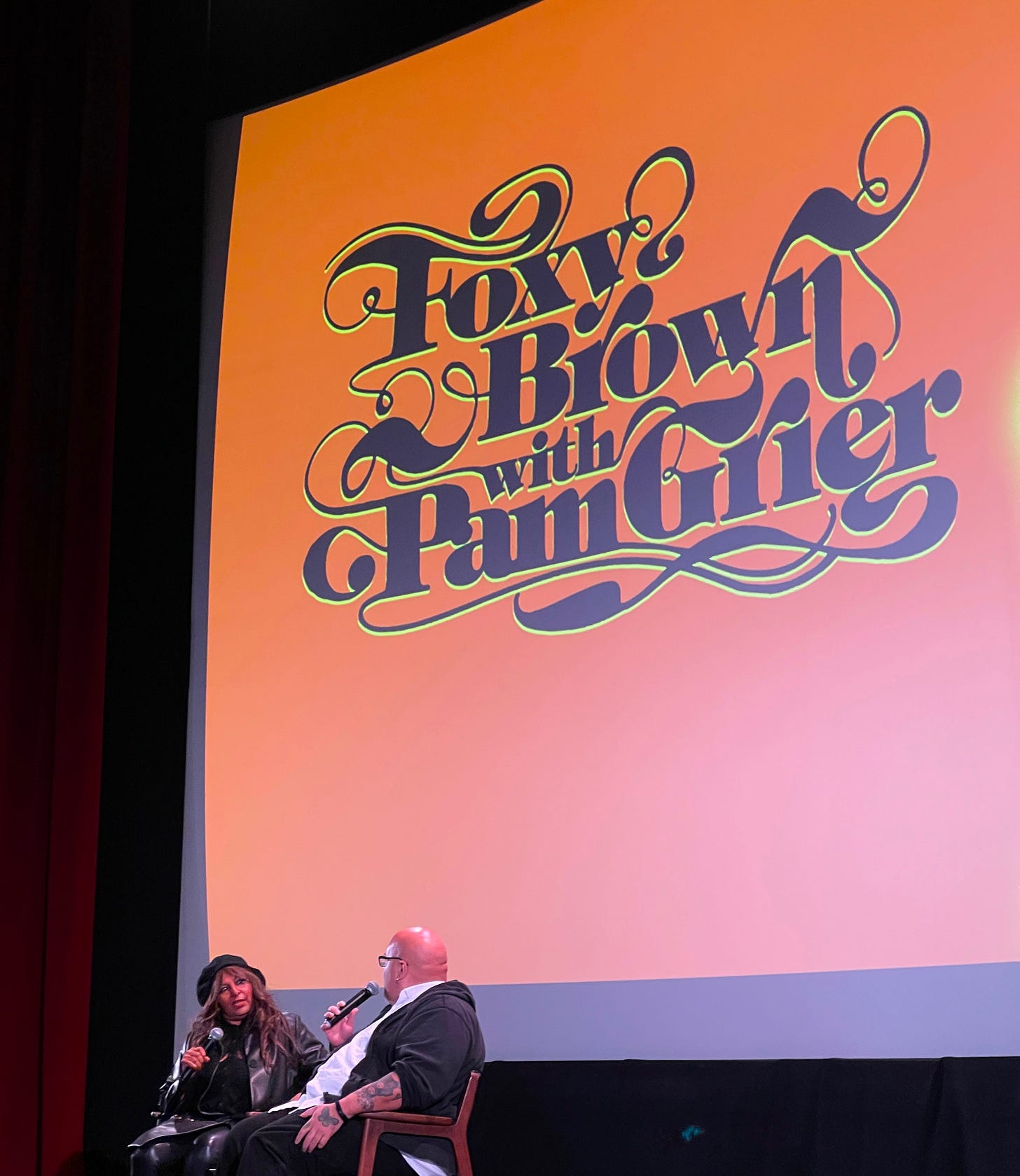

Nilsson cast Pam Grier as Cora. At the time, Grier was in an intermediate career phase, between her ’70s action-hero debut and her iconic ’90s turn as Jackie Brown — always working, but often in supporting roles.

“Rob Nilsson I met through Sundance,” she told me in 2024, as she was getting ready to introduce a 50th-anniversary screening of “Foxy Brown” in Portland. 22 “I was doing a project for the Sundance Institute.... They thought I’d be perfect, because I’d get some financing at the time. And I wanted to explore working with other actors that you may not ever get to work with. If I’m in town, and there’s a show going on? I work for lunch. Because they’ll get financing and everyone gets a job. When I work, maybe a hundred people work....

“At the time there weren’t a lot of interracial romantic comedies or dramas, and I thought it would be very bold of them. And the fact that they had these really sexual scenes was like, ‘Wow, this is indie. I like this.’”

She was also a runner. “I ran mountains. [Bruce] ran marathons,” she told me. “I drove people crazy. When I came to L.A., I was running up Sunset Boulevard to Sunset Plaza to the top, above Jim Brown and all these actors’ homes. And they used to say, ‘There’s a black woman that runs and hikes up and down this road. Who is she? It was a crazy woman.’ It was me.”

Nilsson found his Coach Elmo through sheer Hollywood luck. He ran into one of his acting heroes, John Marley — star of John Cassavetes’ “Faces” — in Schwab’s Pharmacy in Los Angeles, where (according to Tinseltown myth) 17-year-old Lana Turner was discovered hanging around the soda fountain in 1936.

And in a bold swing, Nilsson took a real chance on casting legendary union activist — and non-actor — Bill Bailey as Wes’ father.

Nilsson was friends with Bailey, who had served in the Lincoln Brigades during the Spanish Civil War, climbed a mast to rip a Nazi flag off the German liner SS Bremen in 1935, and survived a 1950s blacklist. Despite all that, the idea of playing a variation on himself in a movie gave him pause.

In the commentary track on the long-out-of-print “On the Edge” DVD, 23 Nilsson recalls Bailey balking at the whole idea: “He claimed, when I wanted to cast him in this role, that it was absolutely a mistake, that he couldn’t act at all. He’d completely disgrace us. He’d forget everything. He knew nothing.”

Bailey did it anyway. And while it reportedly took patience, editing, and a few extra takes to pull the performance out of him, the overlap between Bailey’s real biography as an aging radical longshoreman and his character’s gives Flash an authentic, gnarled energy that couldn’t be faked.

“In the movie, he talks about ‘Bloody Thursday’ — well, he was there,” said Kissin. “Bill Bailey’s autobiography is amazing. Bill and his circle — blue-collar San Franciscans, longshoremen.... There was a progressive mindset and working-class pride. And all those people are gone now.”

Foreshadowing the rest of Nilsson’s career, nearly every other role in the movie was filled by an amateur whose personal biography aligned with the character’s, or by someone Nilsson knew personally.

“Work with comrades and friends,” Nilsson told me. “Keep the friends. Don’t let commerce get in the way.”

Fair warning: I’ve researched this movie off and on for the past six years, and this is one of those moments where my desire to boil the research down into a pithy essay is an exhausted salmon, swimming upstream against the trivia barnacled to my brain. Anyway, here’s a bulleted, footnoted list of “On the Edge” casting choices that illustrate the last two paragraphs.

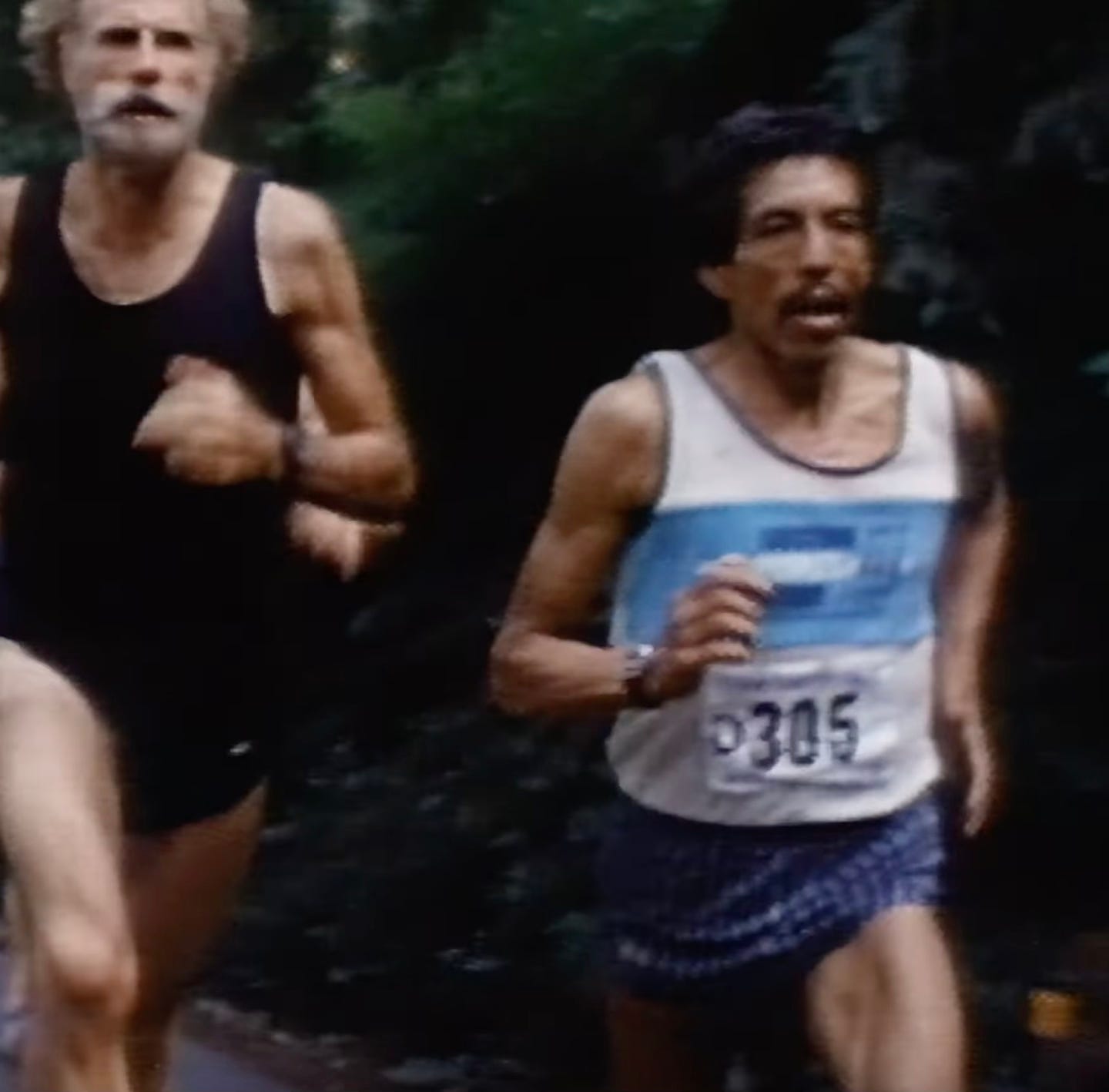

• The runners Wes meets in the VW bus — the same runners who help him to the finish line later — are played by actual Dipsea champions Donna Andrews 24 and Don “Mr. Dipsea” Pickett; 25

• In the back of that same VW bus is Jennifer Biddulph, who (with future husband Brian Maxwell) would go on to found PowerBar a few years later, essentially creating the modern energy-bar industry;

• The climactic Cielo-Sea race field is crowded with Nilsson’s fellow Tamalpa club-runners, a pack of wiseacres who in many cases continued competing in the Dipsea for decades after; 26

• Wes spends a good chunk of the race running alongside the great Sal Vasquez, a seven-time Dipsea winner who turned to running after a struggle with the bottle, a relentless champion widely considered the Dipsea’s Michael Jordan;

• 1970s middle-distance legend Marty Liquori plays himself analyzing the race on local TV station KRON San Francisco;

• Nilsson’s high-school track coach Chuck Crawford pulls the Cielo-Sea starting gun;

• Wes crosses the finish line with Garry Bjorklund, famous for qualifying for the 1976 Olympics despite losing one of his shoes during lap 14 of a 10k that included Frank Shorter and Bill Rodgers;

• Beloved then-Dipsea Race Director Jerry Hauke — by all accounts an unimpeachable good sport, widely credited with saving the Dipsea Race during its difficult middle age — plays one of the officials trying to tackle Wes;

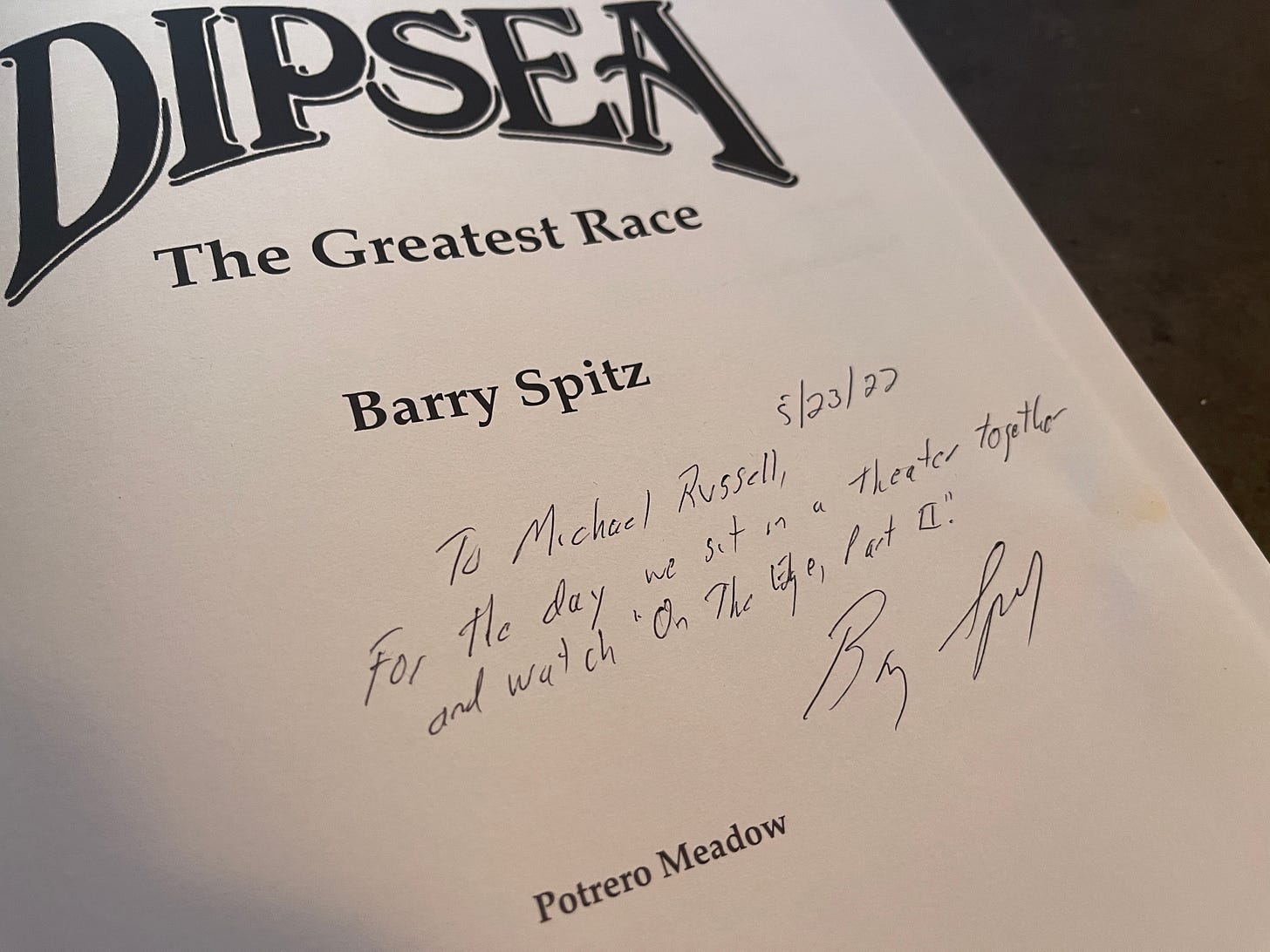

• Barry Spitz — then in his second year as Dipsea Race finish-line announcer, plays the Cielo-Sea finish-line announcer. Spitz wrote the essential history book Dipsea: The Greatest Race and co-owns the very sort of timing clock the rioters toss in the ocean. He earned his SAG card saying one of the film’s final lines: “I don’t know what to tell you — I’d like to see the guy finish”; 27

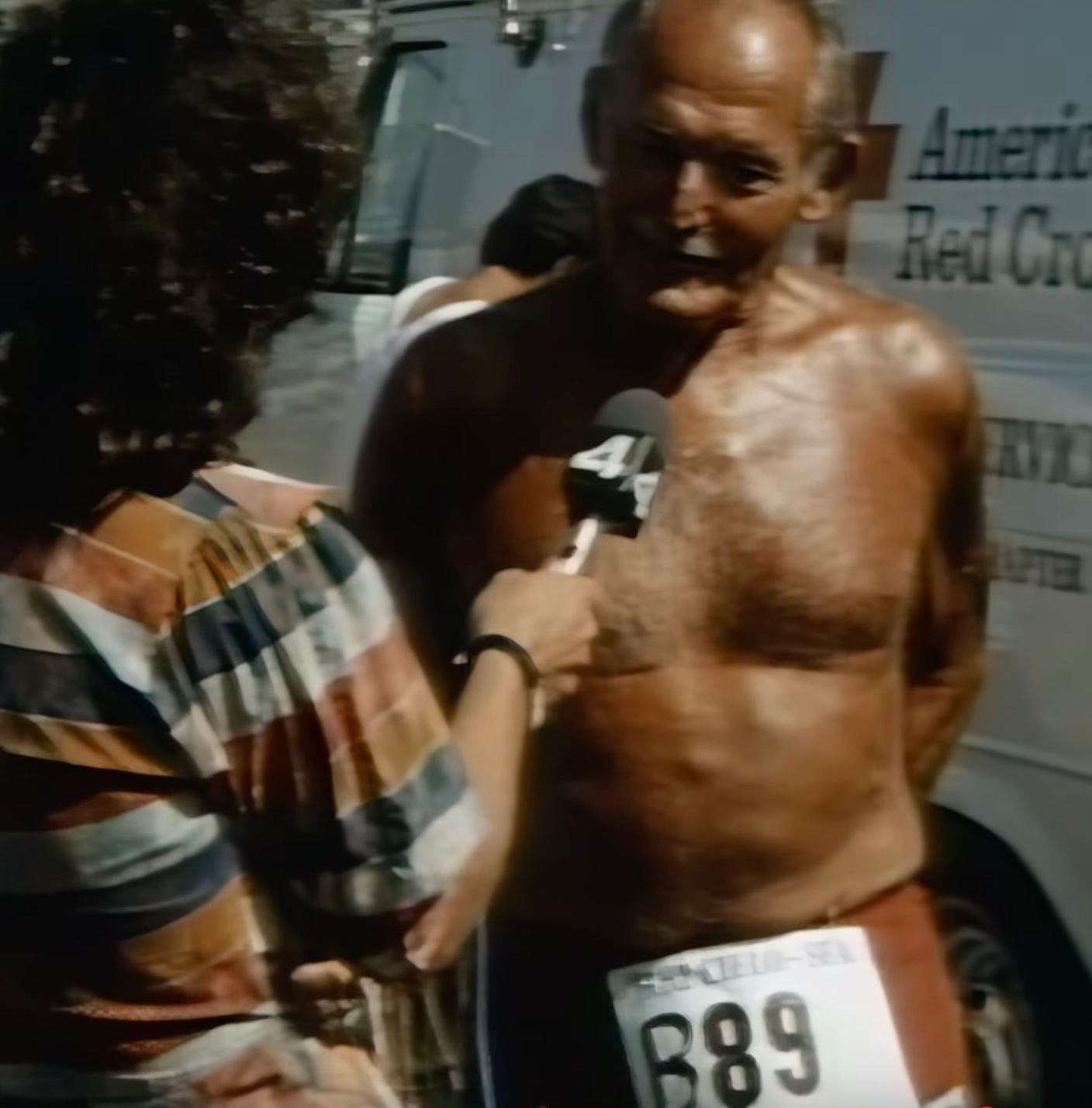

• And dear God here’s 75-year-old local legend Walt Stack, founder of the Bay Area’s Dolphin South End Running Club, often seen running bare-chested across the Golden Gate Bridge, his body a quilt of sailor tattoos, a former hod carrier described by Nilsson as “a Communist until the day he died — he never got the word about Stalin,” telling dirty jokes to a TV reporter at the Cielo-Sea starting line. Stack died 12 years after filming this scene, a runner to the end. The year before filming, he reportedly completed the Ironman Triathlon in its record slowest time; Wikipedia informs me he rode the bike section on a bicycle with a “granny basket” and stopped for a waffle breakfast before finishing. He was the star of Nike’s very first “Just Do It” commercial.

It’s another time capsule, populated with the idiosyncratic characters that emerged during the 1970s running boom.

“Today’s training methods and the advances in our understanding of physiology, nutrition, et cetera, requires a kind of total, single-minded focus to succeed at the highest level in running,” said Kissin. “We frankly didn’t really think that way. I think that the sport was more interesting then, because the people were more interesting.

“One of my training partners was Duncan MacDonald, a Stanford graduate, some years ahead of me, who during my time there was a resident at the Stanford Hospital. As a resident and a married guy with a baby, this guy set an American record in the 5,000 meters, made an Olympic team. And today, people are, like, ‘professional runners.’ They get some shoes.”

As Nilsson built his cast and crew, he also scraped together a budget.

“They raised the first $300,000 by going to races around the country and seeking contributions of as little as $10,” Dern told the Associated Press during the 1986 press tour. “This picture has more than 3,000 backers.”

While this Kickstarter-before-Kickstarter quote makes for good copy, most of the budget came from larger-scale investors. Nilsson remembers “it took John Stout and I three years to raise the money with independent sources. And then, later on, another company came in with Roland Betts and International Film Investors, Inc., I think it was, for finishing money.” According to Kissin, “Half the money was from video presale and advance on distribution rights.”

A major budget windfall came from Dern himself, who by now was all-in: He agreed to work for a quarter of his usual $400,000 fee. In the months before filming, he also lost a “reverse DeNiro” amount of weight, as Kissin described it, to give Wes a “camera-ready” version of a trail-runner’s rangy build.

By the time cameras rolled, they’d raised $1.6 million. They’d hoped for $2.5 million. Nilsson’s father’s Winnebago was the closest thing Dern would get to a trailer.

Principal photography took place over five or six weeks, in the summer and fall of 1983.

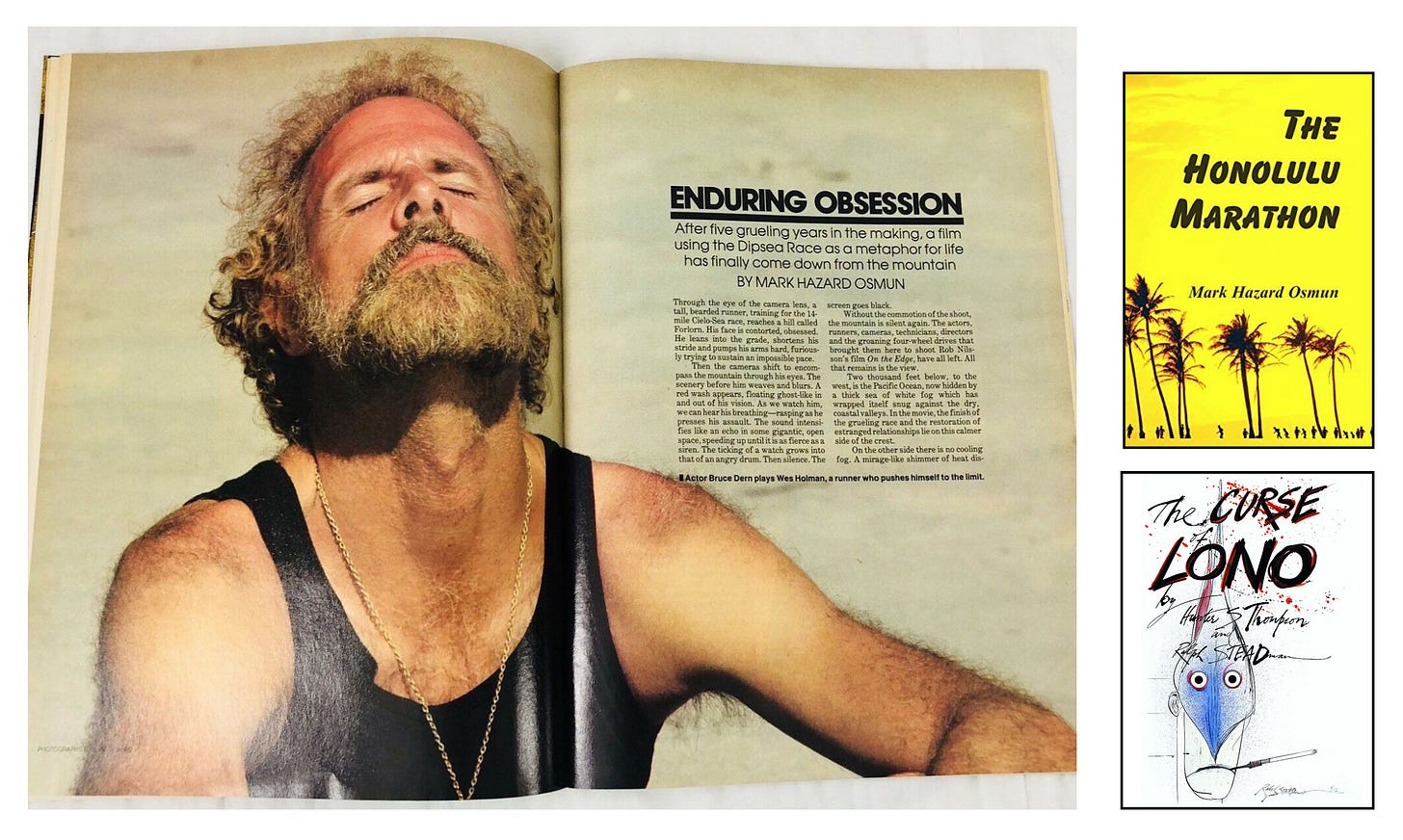

Mark Hazard Osmun was there for two of them, taking notes.

Osmun was hanging out on set to write a story for The Runner — a long-vanished running magazine that competed with Runner’s World, only to be absorbed into Runner’s World in 1987. 28

Osmun, then 31, was a freelance writer and author of 1979’s The Honolulu Marathon, a terrific book of New Journalism reportage on Hawaii’s running boom. It reads like the saner cousin of The Curse of Lono, Hunter S. Thompson’s loopy 1983 book about covering the 1980 Honolulu Marathon for a Nike-backed magazine called Running.

Osmun had been up for that very same writing gig before Nike decided to assign it to the godfather of gonzo journalism, and he happened to be in Hawaii while Thompson was reporting the piece. The two were introduced at Honolulu Marathon founder Dr. Jack Scaff’s “carb-loading party” and became friends. Osmun recalls hanging out with Thompson at a friend’s house along the marathon route’s 22nd mile, watching the runners and drinking Bloody Marys, while illustrator Ralph Steadman drew a sign for the passing runners that read “Nuclear War — Race Cancelled.”

“Hunter asked me if I felt guilty not being out there on the course,” Osmun remembered in 2024. “I threw back his own quote, from a book signing he’d showed up late to: ‘I’m not rich enough to be guilty.’” 29

Nilsson gave Osmun nearly unfettered access to the production (save the closed-set sex scenes). Osmun’s resulting story, which finally saw print in December 1985, is by far the best-written piece of journalism about the film. It’s also a time capsule in its own right — hailing from a time when print running magazines had actual budgets to send journalists on multi-week adventures that resulted in thousands of carefully considered words.

“The system does not value peculiarity of vision,” Nilsson tells Osmun at one point. “But I’m a desperate man with something to say. And I’m going to say it regardless.”

When I talked to him in 2022, Osmun remembered the great weather. He remembered watching Dern run on train tracks while holding a rusty oil tank over his head, part of a training montage. He remembered tagging along with Nilsson as he showed “Northern Lights” to potential investors — proof Nilsson did, in fact, have something to say, if not the money to say it. He remembered sitting in on what he described as “so-called” casting sessions, “which were just conversations Nilsson was having with people that he knew.”

At Nilsson’s behest, Osmun even helped fill the frame with unpaid extras by playing a reporter covering the finish line. When the finishers and rioting fans ran into the ocean, it seemed to Osmun like “they were also kind of running into the ocean to celebrate, because they were having a good time making the movie.”

Osmun had a single, long afternoon interview with Dern, while they were filming what I’m pretty sure was a dinner-party argument at Flash’s junkyard home. “Dern struck me as a really intense guy,” Osmun remembered. “He’d say whatever was on his mind. He’d say things where most people would probably say, ‘Oh, this is not for print.’ But not Bruce.”

It’s all there in the piece:

“There were no individuals on our track team. But it is an individual’s sport. All my life I’ve always wanted to be part of a team. But I always ended up by myself,” Dern says, then adds despondently, “I don’t know why.

“Every scene is difficult,” he adds, his voice bitter. “Every time you have to cry, every time you have to make love you expose the central nerves of your heart so the public can see it. You never get it back. You leave pieces of yourself in every film. Movies are the most brutal, unfair business there is.”

In a moment, Dern is called back to the shack for another take. The scene is supposed to take place at night, and so all of the shack’s doors and windows have been sealed, making it as hot as an oven. Dern gets up and steps back into that inferno without saying goodbye.

If Dern had less of a filter than usual, it might be because in addition to acting his ass off, he was running his ass off, much of it uphill.

In press interviews for the film, Dern estimated he logged somewhere between 400 and 500 miles during the production. Some of those miles were part of a daily tune-up workout he did on top of his screen mileage.

“I ran a half-hour every day on that movie,” Dern told me. He said the production rented him a house owned by tennis legend Rosie Casals (“one of the three or four more competitive dames I ever met in my life”), and every morning he’d “go down to a track, and if there wasn’t a track, I’d find a strip of road that was like about 100 yards long, without traffic to run me over. And I would run intervals — 100 yards down at a fast speed, jog back. And I’d do that for 30 minutes, and then I’d go to work. So I wasn’t on my feet that long, but I was upping the ante.” 30

In the May 4, 1986 Oregonian — in a Sunday arts feature I remember reading at age 16 — Dern told writer Ted Mahar he used running as a sort of throttle for his performances: “If I’m playing a guy who’s really up, or is driven in some way or has some kind of energy that has to show, well, I run at the end of the day. Then I can use my own energy to fuel the character. But if I’m playing somebody who’s kind of mellow, laid-back, not an offensive character, then I run in the morning to get rid of all that energy. I can vary my running to help my character, too, like, if he’s really tired, or beat, I can run really fast in the morning to produce a different kind of tiredness.”

This partially explains the surprising moments of quiet in Dern’s performance. But Nilsson was also doing his part to find and create those moments.

“A lot of that was Rob Nilsson,” Dern told me. “He would say, ‘Go over and rest there until the next shot,’ and then he would leave a camera on me while they were setting up another shot. And that camera was just filming me idling the time. That’s why it doesn’t look scripted.” 31

“I think, in some of his roles, he’s sharp — he’s got an angular and sometimes angry persona,” Nilsson told me. “I wanted him to be like a lion. He grew a beard. I wanted him to stand in front of a mirror and roar — to have this outward milieu surrounding him of light and purpose and capacity. I remember how well he did with that....

“We’d be shooting in the cold or late light, with wind and stuff, and he’d be standing off somewhere for a wide shot — a hundred yards away or more. And the entire time, he was absolutely attentive, because he never knew when he was gonna get called on to run.... This guy taught everybody what it meant to be on the dime. It was a lesson in professionalism I’ve never forgotten.”

“I think, in terms of effort, ‘On the Edge’ is one of the three best movies I was in, in terms of teamwork,” Dern told me. “That was a miserable fucking movie to make. Because, you know, [Nilsson] says, ‘Go down, come around the bend, try and run like a 15-second 100 up the hill.’ Oh, for Christ’s sake. Well, you do that seven or eight times....”

In his 2007 memoir, Dern had kind words for the teamwork. “I met the Marin film community. These people can make movies, but they make a different kind of movie. It’s guerrilla filmmaking.... They know how to move fast, they know how to move well.” 32 Dern wrote that cinematographer Stefan Czapsky “could do things with no light, or a little bit of light, or natural light, and, amazingly, was not threatened at all by another cameraman working side by side with him who shot the running stuff, running with me at six miles an hour.”

That cameraman was Stephen Lighthill, one of Nilsson’s Cine Manifest comrades. He’d gotten his start as a news cameraman in the 1960s for San Francisco’s CBS affiliate KPIX, and his ability to grab a shot on the go is one of “On the Edge”’s secret weapons.

“He had huge calves,” Dern told me, “and when he was filming close-ups of me running downhill, he was running downhill backwards. He had two guys on him, but if he goes down, they’re going to go down. He was big — he looked like he just came off a whaling boat or something. But he was excellent. Rob knew some people.”

One sequence shot by Lighthill, with a younger racer chasing Wes through the forest, looks like one of the “spook-a-blast” POV shots from Sam Raimi’s horror comedy “Evil Dead 2” — with Lighthill jumping over logs and ducking under branches to keep up. His scrappy camera work absolutely eats the lunch of nearly every other film then trying to cash in on the running boom. 33

In a 2018 interview with American Cinematographer, Lighthill remembered that he

“learned a lot from Stefan [Czapsky], and one of the things he taught me was that the job of the cinematographer is to give bad news to people all day long, but do it in a way that keeps everybody calm. The instructive moment was when we were shooting a scene on Mount Tamalpais that required Bruce Dern to stop running and jump into a pond. I was on a rig out over the water, and Bruce got in the water and did the scene. He was almost blue; it was freezing cold. Stefan asked me, ‘How’s the shot?’ And I said, ‘Well, it’s not perfect. Here’s what happened…’ and Stefan said, ‘Look, the bottom line is it’s not right, and we have to get it right.’ I said, ‘But Bruce is freezing,’ and Stefan said, ‘That’s not your concern’.... Stefan walked over to Rob and said, ‘We’re doing it again.’ We did it again and got it right. I learned then that your job is to serve the story, and part of that is telling people exactly what you think about what you’ve shot.”

Nilsson knew the landscape would be a major character in the story. “I demanded that it be visual,” he said. “I would much have preferred, for example, that the race end at sunset.” He laughed. “Unfortunately, they weren’t willing to, or we weren’t able to, or we felt that would be ridiculous.” He also considered shooting the entire film with a gliding Steadicam (“I thought every shot should be in motion”) but it didn’t pan out.

When I asked him about any “tricks and techniques” he and his crew used to get their running footage and box above their budgetary weight, he replied: “Well, there weren’t any tricks. I went over the mountain with a fine-toothed comb. I knew what the locations were gonna be way before the movie. I’d been running the Dipsea Race since I was in high school.”

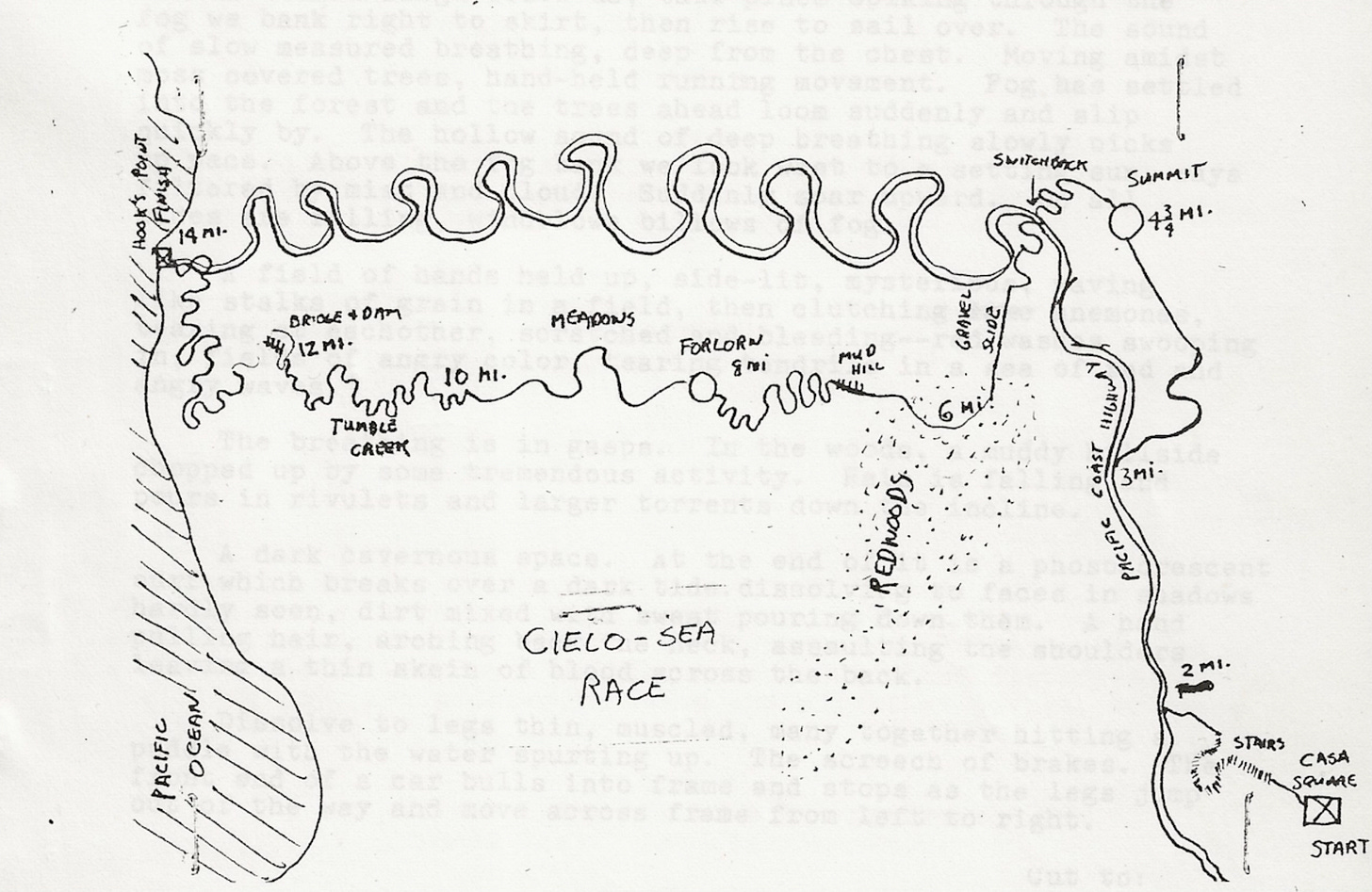

Nilsson hand-drew a tiny map of the Cielo-Sea course in his rough-draft screenplay, complete with fictitious scenic markers named “Gravel Slide,” “Mud Hill,” “Forlorn,” “Tumble Creek,” and “Hook’s Point”; he says you can map it to existing trails and (more or less) run it for real.

While the movie’s 14-mile Cielo-Sea is clearly inspired by the 7.5-mile Dipsea, right down to aping its logo design, it also steals some of its overwhelmingly scenic race course from the Mt. Tam Hill Climb, held every Labor Day and founded just a couple of years before “On the Edge”’s principal photography. Like the Dipsea, the Hill Climb starts in downtown Mill Valley, but rather than heading to Stinson Beach, runners scramble to reach the mountain’s Gardner Lookout on Mt. Tam’s East Peak, by any route they see fit. Together, these two races — each an uphill free-for-all — provide a buffet table of vistas.

Dern runs around Gardner Lookout in the film, and it’s a lovely aerial shot, the camera circling around the peak while Dern crests the summit in an opposing arc. “We got all this wonderful aerial photography,” Kissin remembered. “You’d just do that with a drone now. At the time, you had to get a helicopter, a rig, and a crazy Vietnam-vet helicopter pilot. It was expensive and it took lots of planning to make maximal use of it.... There were no cell phones. We had a satellite phone. It sounded like you were calling from the moon.”

Meanwhile, Grier made her way to the set even when she wasn’t working — hanging out, taking her own notes on the Marin film community. “I have memories of them saying: ‘You’re off today — why are you here?’ Because I’m stealing your ideas. I’m gonna write and direct one day, so I need to see how this works.... I was always the student.” She told me Dern “was very humorous off-camera, which I wanted to see more in his character’s subtext.... Rob didn’t see that.” 34

It wasn’t the only avenue unexplored. “Czapsky wanted to photograph Dern running naked over the hills, maybe with starlight, or something like that,” Nilsson remembered. “Dern running naked on a ridge at sundown! And of course, when you think about it, yeah, why not? Maybe we didn’t have time or the money to get Bruce to agree to it. I should have made sure it happened. But I didn’t.”

The most surprising thing I learned about this sun-kissed, big-hearted film that brought me so much pleasure and inspiration over the years is that its editing process was long and unpleasant — and left a few people with complicated feelings about the whole project.

“Pam was in the first cut of the picture, which ran three hours,” Dern told the Seattle Times in 1986. “Now it’s 91 minutes.... Those last 15 minutes were always magical, and every time something was cut out of the picture, you could see that it helped. A year ago this movie didn’t work. Now it does.”

Thanks to Nilsson, I’ve read the screenplay draft I assume aligns closely with that early cut, and saw what Nilsson was going for. But a screenplay is not a movie, so I want to tread lightly here. Several people involved in the production said the edit of the film containing the full Wes/Cora relationship presented three hurdles.

First: It played like two films operating on separate tracks — a sports movie and a relationship drama — cut together with almost zero overlap. To a degree, that’s on the page. In the script I read that’s closest to the shooting draft, Cora never meets Wes’ coach or father. All her scenes are two-handers with Wes, and Wes never discusses her with anyone else.

“In the story, I was never sure where Rob was pitching his tent,” Dern told me.

Second: Despite strong and characteristically fearless work from Grier, she and Dern didn’t spark onscreen. “One of the fundamental problems was that there just wasn’t that much chemistry between them,” said Kissin, “so it didn’t really come to life.”

Third, and most crucially: Despite taking this cut to festivals, they couldn’t sell it. 35

“There was a movie in ’84, but we couldn’t get it distributed,” said Kissin. “Rob was really not willing to give up on his original idea.... But we had advance money from various entities, professional film investors. Part of our funding came as an advance from an investors’ group that had distribution contracts. These numbers seem small now, but back then? A million six was just a huge amount [for an indie film].... The politics around it were difficult and emotional. But eventually, it was like, ‘Hey, we’ve got to get this thing released because we want our money.’”

Nilsson had final cut, but, as he put it to me, “There were a lot of voices in the room.”

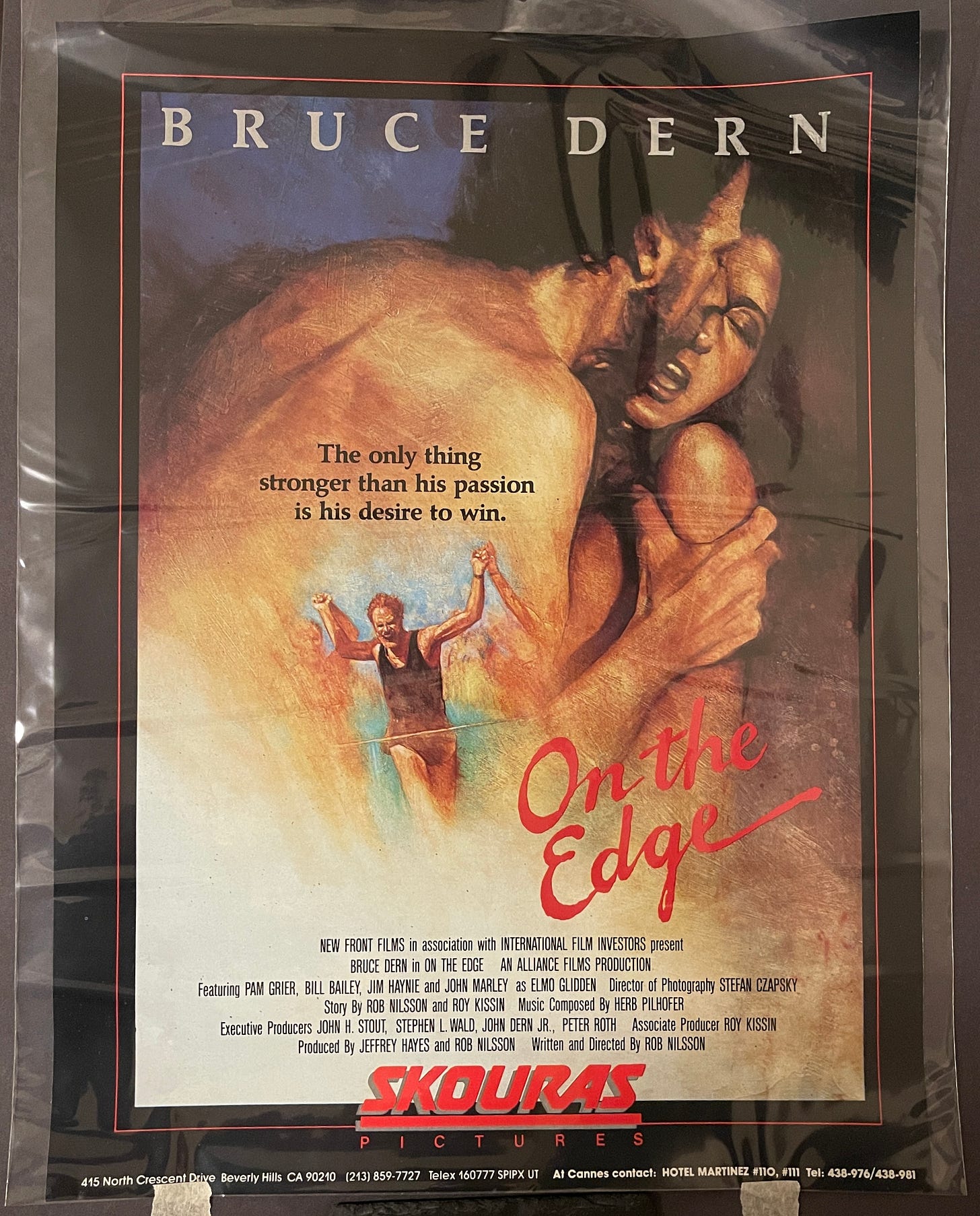

In an effort to help Nilsson secure a sale, producer/distributor Tommy Skouras took a cut of the film to Cannes in 1985. He also took out a full-page ad in the May 4, 1985 issue of Screen International. The ad reflects earlier dramatic priorities. It’s a painting of Wes and Cora in a nude embrace, runners appearing in a smaller inset. The tagline: “The only thing stronger than his passion is his desire to win.”

Nilsson started testing different cuts of the film at festivals — dialing back the Wes/Cora relationship in one version, deleting it entirely in another. I gather the edits were hotly debated. Director and leading man were each deeply invested. Dern, a fanatic for the sport, would only make one running movie because of what it took out of him. Nilsson, meanwhile, had poured gallons of autobiography into his script.

“Bruce was playing Rob,” Grier told me. “Rob’s a runner.”

The behind-the-scenes conflict spilled out into the press a few times in 1985, as various edits made their way through the festival circuit.

In his magazine feature for The Runner, Mark Hazard Osmun briefly mentioned “bitter personal and professional differences ... over the importance of Cora.” Months earlier, Dern, characteristically free of filter (shockingly so, given the movie hadn’t secured a release yet), openly discussed the differences in an interview with Runner’s World.

“As I started making this movie, I began to think, ‘How much is Rob Nilsson, how much is Wes and what’s left over for me to do?’” he told East Coast Editor Amby Burfoot. A few paragraphs later, he said, “I don’t want to be a diplomat because that’s not fair. I feel the sex scenes are uniquely shot, uniquely designed and uniquely placed, but there is an anger in them that troubles me. It troubled me when I first read the script and I tried to sit on it a little as a character....

“If the movie suffers, it suffers because it is too ambitious. It tries to wrap up a relationship with a coach he hasn’t seen in 20 years. He tries to solidify a relationship with a father he hasn’t seen in 20 years. And then it tries to have me have my first full-blown love affair and have a beginning, middle and end and then I’m supposed to come home as Jack Armstrong. Know what I mean? Give me a break.... Despite all this, it’s a much more than worthwhile film. It’s a courageous attempt at exposing a part of the athletic arena.”

Elsewhere in that same issue was a mixed review of a Wes/Cora festival cut of the movie, written by “senior editor and resident film critic” Bob Wischnia. Wischnia declared it “simply the best movie ever made about the sport of running,” but also called the dialogue “cliche-ridden” and asserted that “the late John Marley ... is so bad as Dern’s coach that I couldn’t help but wonder whether he died before or after he made the film.” That last zinger is so rude, lame and incorrect that it manages a sort of bullseye of wrong — landing in the perfect intersection between critical malpractice and pointless cruelty.

In June 1985, a cut of the film with Grier’s role completely removed played at the Seattle Film Festival. Unfortunately, her name appeared in the festival program. The San Francisco Chronicle contacted Grier and Nilsson for comment. At the time Grier was in the middle of a recurring guest-star run on “Miami Vice,” and in a supreme act of graciousness, she told the reporter deleting the role was her idea. (It wasn’t.)

“I loved my role of a strong young woman who became a kind of truth serum for Bruce,” she told the Chron. “He learned about himself from her. But, in the end, I thought she detracted from his story.... I want Rob to make the best film possible. For the festival that meant cutting me out completely.”

“Nothing’s definite yet,” Nilsson said. “We’re still experimenting with different versions. Pam may be back on the screen.”

When I brought up her graciousness, Grier said, “I had to be — it’s his story.” A few minutes earlier, she’d said, “I wanted to work in that aquarium. I wanted to throw chum in the water and see what happened, you know?”

The writer David F. Walker (a mutual friend) entered the green room. He was there to interview Grier onstage ahead of the “Foxy Brown” screening. She smiled and immediately started flipping him shit, almost certainly happy to change the subject before stepping in front of an audience to celebrate one of her biggest hits.

“Oh, he’s ready,” she said when she saw Walker, asking him, “Did you wear a cup?” They danced together after he invited her onstage, to a roaring full house.

In the end, audiences decided the fate of “On the Edge” — in the editing room and at the box office.

A Pacific Northwest evening screening of a Cora-free cut was the deciding factor.

“At the time, I was thinking about whether or not the stories of Wes and Cora jibed,” Nilsson told me. “You’re kind of a conductor. You’re trying to bring the thunder and lightning down, and you’re never sure, at least the way I work.

“That night, I was in conversations about what to do, and got a standing ovation — one of the few in my life — for the film as it was. That determined my decision to strip down the film to the running story.

“However, it doesn’t mean that I today think that it was the right decision. Talk about a talent and a mensch and a wonderful person. Pam. I still have a twinge about that.”

Nilsson, now crafting a pure running movie, shot additional footage and reorganized scenes, relentlessly shaving the whole thing down to the “tight 90” I saw in 1986.

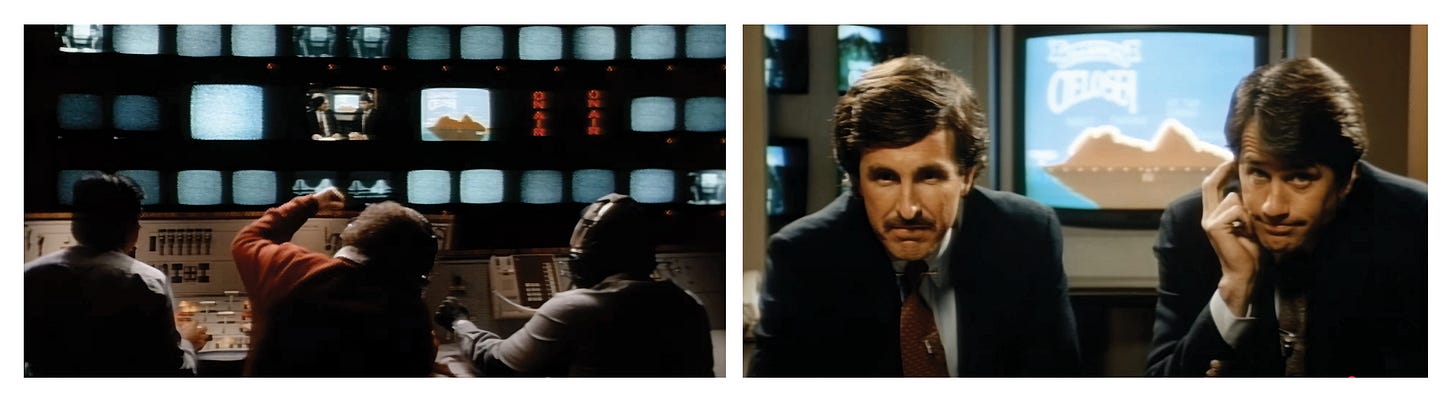

During the postproduction odyssey, he traded a bit of plausibility for narrative clarity — bringing Marty Liquori and KRON sports anchor Mike Cerre into a TV studio to film some clarifying exposition in the guise of a sports broadcast.

Playing themselves, Cerre and Liquori offer color commentary on the increasingly anarchic Cielo-Sea, discuss Wes’ ban, introduce the racers who help him, explain the handicapping system, and just generally add a layer of context to the finale. 36

“When we put all this footage together of the race, it really didn’t quite work somehow,” said Kissin. “Maybe I’m imagining this, but my memory is that was my idea to bring it into the television studio and have that coverage. That made it all work — the ability to seamlessly tie together all the stuff that was ‘real time’ with lyrical, aerial, omniscient-viewpoint stuff.”

Reading the draft screenplays provided one more surprise. The moment that so captivated me in 1986 — Dern bounding up Bolinas Ridge, spinning in delight at the top — originally appeared much later in the movie. This joyous sequence was written as part of Wes’ final awakening as a running “artist.” (This explains why Wes is seemingly in great shape when we first see him run, but struggles a couple of scenes later when he embarks on his year of training with a slow, wheezy jog.)

To be clear: I love this “commercial” edit of the film wholeheartedly. Just for starters, my coach wouldn’t have taken me to see an erotic-drama version of “On the Edge” at age 16, I never would have run the Dipsea Race (twice, poorly), and I wouldn’t be writing this today. I would have been denied an entire adventure, up to and including comparing notes with Dern on our schoolboy 800-meter training strategies. 37

That said, the saga presents a fascinating might-have-been for adult me, who spent a few years writing about movies for vanishing amounts of money.

“A good friend of mine, also a filmmaker, believes that I made a bad mistake,” Nilsson told me. “He loved the version with Pam Grier in it.... But I can’t give any certainty. All I know is my respect for her. And we’ve talked since that time. She’s been a friendly presence in my life. And I can’t say anything more than that, other than that if I made a mistake, okay, I made a mistake. I can’t judge it properly. Even now, I’m still too close to it.”

Personally, I want both versions out there.

The sports-forward, romance-free version of “On the Edge” was finally released theatrically on May 2, 1986, nearly three years after principal photography wrapped. Reviews were mixed-to-positive, with The New York Times and Roger Ebert (in print and on TV) among its key champions.

But a theatrical audience failed to materialize. IMDb lists a North American gross of $440,438. “It only played in theaters for about six weeks total,” said Dern. 38

“At first, we got pretty darn good reviews,” Kissin said, “but people didn’t show up. Proof of concept: Just because you’re a runner doesn’t mean you’re going to go to a running movie, even if it’s got a certain degree of verisimilitude.”

Dern shared his own acerbic take on the film’s box-office failure in 2014, during another interview with Runner’s World. He was fresh off a victory lap for his award-winning performance in Alexander Payne’s “Nebraska.”

“’On the Edge’ didn’t do well, and you know why as well as I do: Runners are cheap mothers,” he told Caleb Daniloff. “If they don’t see it at a screening, they’re not going to pay to see it, and they didn’t get out and embrace it. I thought it was because the movie wasn’t good. No, it’s a good movie about running.” 39

On June 6, 1986, the Marin Independent Journal published an article, “Film puts runners on edge,” in which Dipsea Race organizers openly fretted about the amount of attention “On the Edge” might bring to that year’s running of the event. But fears of a jogging mob proved unfounded. A few days later, in the paper’s post-race recap, race director Jerry Hauke said, “Actually, everything ran very smoothly. The unofficial runners were polite and went where we asked them to go. And the spectators were not too much to handle. It was a good Dipsea.” Nilsson himself finished the race in the top 100. 40

In October 1986, just five months after its theatrical debut, two VHS versions of the film hit home video — the theatrical cut and an “unrated” version with just four of Grier’s scenes restored, a fraction of the full scripted romance. You can find a few fuzzy uploads of the unrated version on YouTube. It makes me root a little less for Wes. He comes off as taking Cora (Pam Grier!) for granted.

And with that, the “On the Edge” misadventure was over.

Except it wasn’t.

The film’s afterlife began a month after its release, at that fretted-over June 1986 Dipsea Race. The winner, Gail Scott, entered at the last minute ... because she’d just seen “On the Edge.”

“Seeing that movie did get my Dipsea fever riled up and that’s why I’m here,” she told the Marin Independent Journal. “I didn’t think they’d let me in, but I called them up and begged and they did.” 41

The film also found its niche audience, thanks to a relatively young secondary market: home video.

“It doesn’t happen so much anymore,” said Kissin, “because the film’s, you know, impossible to find now. But it used to be, all the time: ‘I love the movie. Bought a copy. Cult classic.’”

I’d catch residual echoes of this during my training/research odyssey.

After someone (not me) uploaded a rip of the unrated VHS to YouTube in 2021, “On the Edge” started popping up as a topic on running podcasts hosted by guys with a little gray in their hair.

In 2022, Track and Field History host Jesse Squire brought on his film-professor brother Walter, who pointed out that “usually sports movies are celebrating an individual.... and this movie sort of ultimately turns that on its head.” 42

In 2024, the Just Athletics podcast devoted an entire episode to “a film no one has seen ... the best running movie ever,” declaring Coach Elmo “the greatest running coach on film.” Host Chris Johnson first saw “On the Edge” as a high-school junior, and quoted that “burn/soar” moment just like my teammates used to, only unironically. “I did that all of the time, my whole running life,” Johnson said. “Something about it is kind of helpful.”

Then there was the sponsored ultrarunner and coach, with whom I’d struck up a conversation at a trail-race afterparty in 2021.

“I love that movie!” he said. He’d scored multiple top-10 finishes in the “Quad Dipsea,” racing the Dipsea Race course out and back twice, a spectacular stair-grinding nightmare of more than 28 miles.

“The dude who co-wrote it lives here in town,” I said. “I interviewed him about it. I just turned 50 and I’m gonna try and run the Dipsea this year.”

“Hey, man — it’s good to have that dream.”

Then there was my friend’s father Steve, a retired Mt. Shasta high-school running coach who ran the Dipsea in the 1970s. He’d taken his runners to the Humboldt Distance Running Camp in the early 2000s when they threw “On the Edge” on the projector for “movie night.”

“It was the perfect audience,” Steve told me as we cheered on his daughter, who was competing in a backyard ultra in the Columbia River Gorge. “There were enough of us who knew the legendary status of it and could tell stories afterwards.”

Then there was the guy standing next to me in line at the Mill Valley Post Office, as we waited to mail in our 2023 Dipsea Race applications. He’d run the race 15 times and once finished in the top 100, and during our 10-minute friendship proved a valuable source of intel about gaming the Dipsea application process.

“You know there’s a movie movie about this race, right?” he asked.

“Oh yeah,” I replied. “I’m actually down here to interview the director of that movie.”

“Huh.”

Then there was Dipsea Race historian Barry Spitz, who still includes an “On the Edge” chapter in his book Dipsea: The Greatest Race. He told me the movie captured what the Bay Area “maybe was at that time, which is sort of a haven for counterculture people and people who were maybe thinking a little outside the box.... It’s very blue-collar. There’s a scrapyard, an industrial aspect.”

He’s been involved in a few revival screenings of the film over the years. He said the moment where the racers push an official into the water “always gets cheers.” He shared a particularly poignant memory of Donna Andrews, one of the Cielo-Sea racers in that VW bus. She attended a revival screening of the film in 2015 at the Smith Rafael Film Center —part of the Dipsea Race’s centennial celebration — days before her death from cancer.

“She brought her family to come watch it,” he said. “She died within a week. It was so special to her.... Maybe it’s time to revive it again.”

And then there was my friend Natalie, a former USATF-certified coach. We met in 2013, when I joined her wonderful boot camp for runners; on her orders we used to scamper to various points on Mt. Tabor and wheeze our way through tabata jump-squats.

When I told her about my deeply niche research project, her eyes widened. “I watched that with my dad!” she said. He’d passed away a few years earlier following a cancer battle. She was still sorting through his estate.

Her father was an avid runner and cyclist. He sat her down to watch the VHS with him in the late 1980s. She was a pre-teen.

“I figured it was a typical ‘Dad story,’” she later told me in an email, “something connected with his life that he found compelling and I found eyeroll-worthy.” Her email continued:

As I got to know my father better as an adult, I gained a deeper respect for why he wanted me to view that old VHS tape with him. Dad and Wes Holman were both middle-aged, battling personal demons and challenging relationships. For Holman, it was his father; for my dad, maybe it was missing his father, who died when Dad was 6.

I think Dad was trying to share his own struggles with me — the sacrifices, frustrations, and unspoken desire to prove something, both to himself and the world.

I now own that old VHS since Dad left us.

Did I start running in my early 20s because he showed me “On the Edge”? One hundred percent.

While Nilsson has mixed feelings about his “On the Edge” experience, it is, nevertheless, in its own way, one of the most important movies in his filmography. His reactions to the grueling experience of making it changed the course of his artistry.

Ever since that 1960 screening of “Shadows,” Nilsson’s filmmaking hero has been John Cassavetes, the actor/filmmaker who self-financed intimate, emotionally intense features he directed (and sometimes distributed) himself. Interested in character over everything else, Cassavetes gave free rein to a recurring ensemble that included his wife Gena Rowlands, Peter Falk, Seymour Cassel, and Ben Gazzara. Despite being scripted, these movies (which include “Husbands,” “Faces,” “Opening Night,” and “A Woman Under the Influence”) feel loose, improvisational, unafraid of human ugliness. They’re daredevil jumps over canyons of raw emotion. Several were shot in Cassavetes’ house.

“I think Cassavetes wanted things to be casual, so that you could go deep without embarrassment, or perhaps without fear,” Nilsson told me. “And maybe the embarrassment is what you want, rather than some sort of answer to a question.”

Cassavetes took Hollywood acting gigs to help finance his features. He’s one of the better guest murderers on his pal Peter Falk’s “Columbo,” and of course there are his iconic scumbag turns in “Rosemary’s Baby” and “The Dirty Dozen.” But he distrusted the mainstream, famously saying in Cassavetes on Cassavetes: “There’s nothing I despise more than being entertained.” 43

“He told the truth and took the consequences,” Nilsson said. “One part of him, the actor, was for sale. And he was an establishment actor. The other part — everything he cared about — was a search for the way things seem to be.”

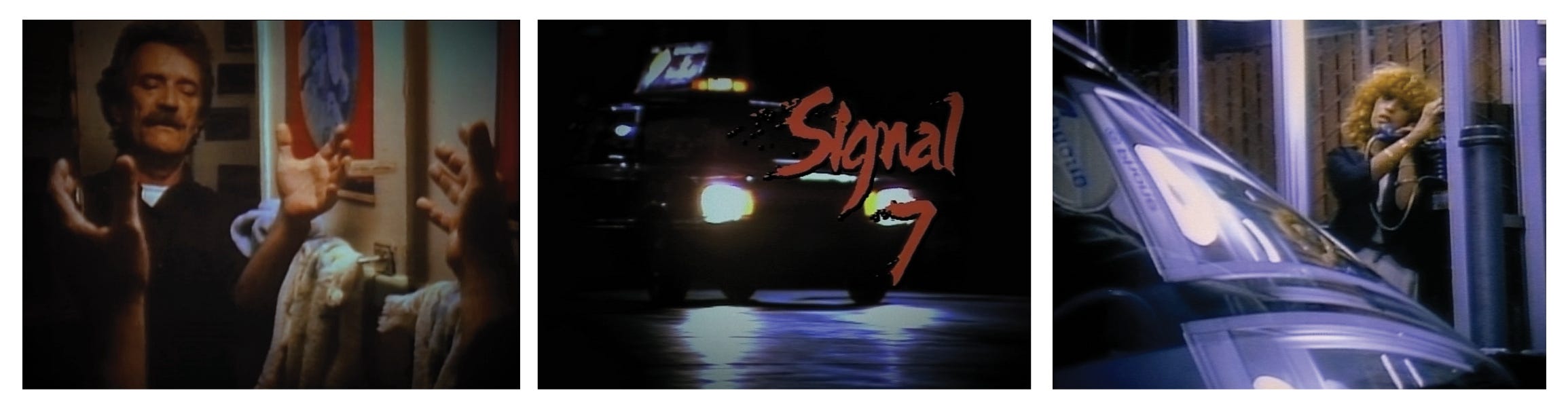

And so: While in the glue-traps of “On the Edge” fundraising and post-production, Nilsson made two smaller movies. They were absolutely free of editorial compromise.

First: In 1983, Nilsson took an unfilmed 1970s screenplay he’d written about his cabbie days, “Marty and Speed,” and used its premise as the starting point for a filmmaking experiment.

He assembled a group of actors and non-actors and shot a completely improvised feature with a couple of video cameras over six days — telling the story of a single night in the lives of a pair of aging San Francisco cab-drivers with delusions of becoming Hollywood actors.

According to a 1985 San Francisco Chronicle story, the production took on the tones of an acting workshop:

After the script was read by cast and crew, they discussed how each scene would fulfill itself. Each man wrote an autobiography, using some of his life experiences and borrowing from others. They rehearsed briefly, improvising dialogue, but rehearsals were kept at a minimum in order to catch the freshness of their responses during the videotaping.

“A local video company agreed to supply the cameras and other gear for a two night trial after which they proclaimed what we shot ‘un-cuttable,’” Nilsson remembered in his book Wild Surmise. So he and his longtime friend and collaborator David Schickele “went into an editing room and cut a couple of scenes in a couple of hours. Then they saw what we were doing.”

Nilsson would sift through hours of improvised video to find the performances, shaping the movie over the course of an epic editing process. He dubbed the filmmaking technique “Direct Action Cinema.”

He then tried something no one had apparently tried before: He printed the video to film.

The final result, “Signal 7,” was completed in 1985, cost all of $150,000, and turned out well enough to get a “presented by” credit from Francis Ford Coppola. It’s a decades-early shot across the bow for digital filmmaking; in its own lo-fi way, it anticipates Michael Mann’s unapologetic “let video be video” aesthetic, seen in the digital cinematography for “Miami Vice” and “Collateral.”